Authorities

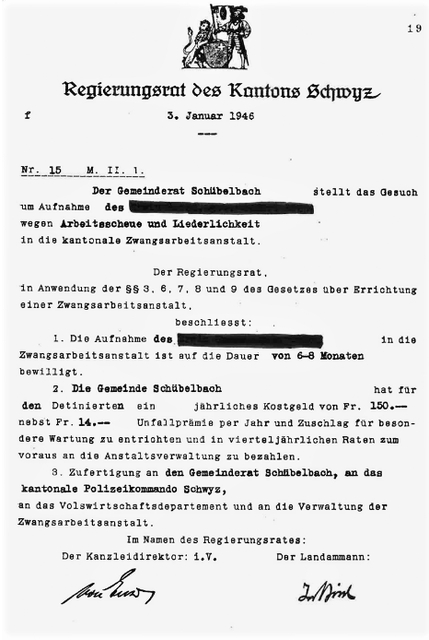

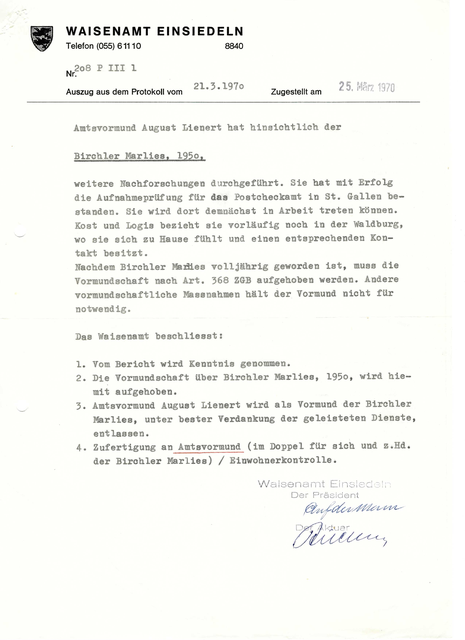

The decision to arrange for social measures lay with the government agencies. They could delegate it to private or church organisations which saved costs. For a long time, individual needs were not in the foreground. Sometimes families were administered for generations.

The Scope for Action of Individuals Was Large

The procedures for official social measures were not uniformly regulated. The scope for action of governmental, private and church organisations was large.

Those who did not conform or fled risked a transfer, an extension of their measures or interference with family planning. Rarely did the affected persons and their families receive sufficient information on the proceedings, potential legal remedies and duration of a measure. To proceed against decisions of authorities was very difficult ...

The Power of Files

A look at the files reveals how people were judged. The not uncommon negative attributions determined biographies and furthered the stigmatization.

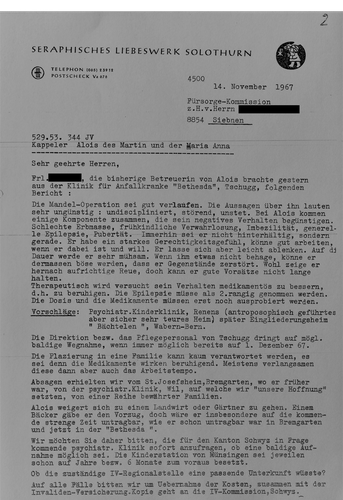

The Seraphische Liebeswerk Solothurn placed catholic children and teenagers, facilitated adoptions, controlled placements in foster care and residential homes and ran own facilities. Alois Kappeler was placed in more than 30 places. The extract of a letter to the welfare commission renders the negative assessments in his files visible (1967). There are attributions such as “bad heredity”, “early childhood neglect” or “imbecility”.

Derogatory descriptions of children, adolescents and adults can be found in many files. They come from various groups such as officials, clergymen, psychiatrists, carers and employees of private and church organisations. Stigmatising attributions had an influence on subsequent evaluations and were given great weight. The so-called file biographies reflect the opinion of the authorities of the time and often had nothing to do with experiences of those affected.

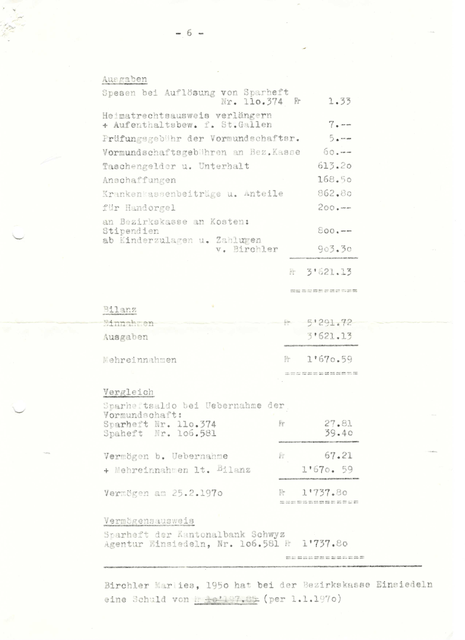

Who Paid for it All?

If possible, the costs for foster care placement or accommodation in an institution were borne by the affected persons or by their family environment (principle of subsidiarity). In many cases low-cost solutions were chosen, but these were often contrary to the needs of those affected.

We Talk in this Film

The Scope for Action of Individuals Was Large

The procedures for official social measures were not uniformly regulated. The scope for action of governmental, private and church organisations was large.

Those who did not conform or fled risked a transfer, an extension of their measures or interference with family planning. Rarely did the affected persons and their families receive sufficient information on the proceedings, potential legal remedies and duration of a measure. To proceed against decisions of authorities was very difficult. ...

Opaque Authorities – a Network of State, Private and Church Organisations

Authorities could impose compulsory social measures by means of cantonal administrative or federal civil or criminal law. The implementation was the responsibility of the cantons, the financing, however, was the responsibility of the home communities. Again and again social measures were decided upon without a decision of the public authorities, especially regarding the placement of children and adolescents. For example, when an unwed mother handed over her child to a private or church organisation due to poverty or social ostracism and the organisation placed the child with foster parents or gave it up for adoption.

Private and church organisations not only acted as placement institutions, but also ran a great number of facilities and assumed supervisory tasks. In cooperation with authorities, they formed a dense network. Those affected were hardly able to fight against these opaque authorities that determined their life. Law, procedures and practices formed a confusing patchwork and varied from canton to canton and from region to region.

The individual freedoms of those affected was insufficiently protected by the law which offered authorities a large scope for decision-making. Fair processes were hardly warranted, possibilities of appeal mostly non-existent, and if for once somebody fought the decision the chances of success were nominal. Not only the proceedings by authorities were opaque for many of those affected: the opaque network of state and private authorities made it difficult for them and their families to understand who intervened in their life and in what capacity. Contacts with child welfare advocates or guardians were rare. Appointed guardians often were responsible for more than 200 wards and were thus overburdened. This reinforced the feeling among those affected that they were merely being administrated.

Record Keeping and Stigmatisation

One instrument for managing people was keeping files on them. In these, various information on a person were recorded. They circulated between the involved authorities, e.g., guardian, poor relief authority and a children’s home. Until a few years ago, those affected had no right of access to file. However, the files had a major impact and often determined decisive moments in their life. This increased the power imbalance between the authorities and those affected.

Personal records not only included allegedly objective facts but also moral judgements about the persons described, such as “debauched”, “difficult” or “neglected”. These stigmatizing attributions were solidified by uncritical adoption and repetition so that those affected were preceded by their reputation. The resulting stigmatisation accompanied those affected often throughout their entire lives and not infrequently their children were also affected. The discrediting judgements about the parents were transferred onto the next generation which often justified renewed coercive measures.

Often, a person’s experience is not consistent with the filed assessment. Nowadays there is the possibility to state the own point of view by adding a correction note to the files if these are still available.