Violence & Abuse

Closed facilities and secluded welfare institutions, insufficient control and supervision: all of this promoted violence and abuse in a society that for a long time offered little space for individual lifestyles.

Dependent and Abused

Psychological, physical and sexual violence was part of everyday life for many of those affected by compulsory social measures.

For a long time, corporal punishment was widespread in the upbringing of minors and still is not explicitly forbidden in Switzerland. Indeed, there were early approaches to a non-violent upbringing: individuals or the media repeatedly reported on cases of abuse, but in the end the perpetrators were often protected and the victims themselves blamed for the violence they had experienced. Supervision and control, if they existed, failed. ...

Sexual Violence in Court – a Rare Case

In the 1940s, in Bad Knutwil, Lucerne, monks of the local “juvenile correction facility” faced trial. They were accused of sexual abuse of adolescents. However, they were by no means the only perpetrators of this kind, but among the few who had to answer for it in court.

“Juvenile Correction Facility”, Knutwil-Bad (around 1930)

The reports of systematic sexual violence against adolescents in the “juvenile correction facility” in Knutwil by monks and priests in the 1940s were not the only ones. Abuses, and at least one suicide that was connected to them, are also known to have occurred during the following years until the withdrawal of the monks from La Salle 1973. ...

The Criticism is Getting Louder

For a long time, the criticism of the neglect und violence during placement in a home or foster care was hardly to be heard. The “Home Campaign” at beginning of the 1970s demonstrates the will to reform that began at that time.

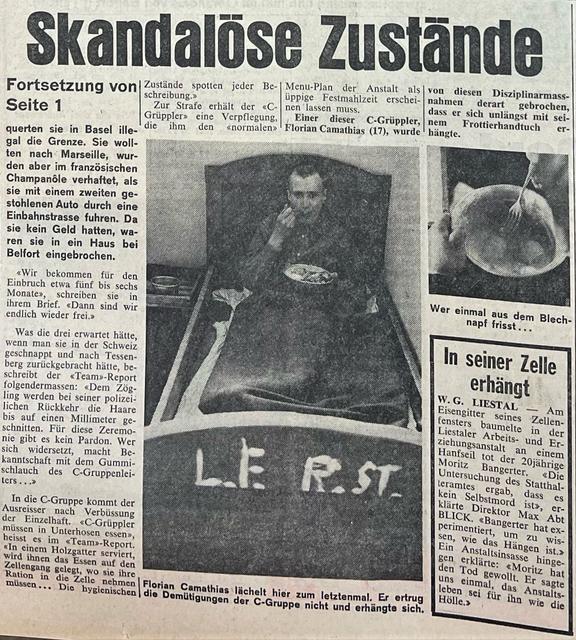

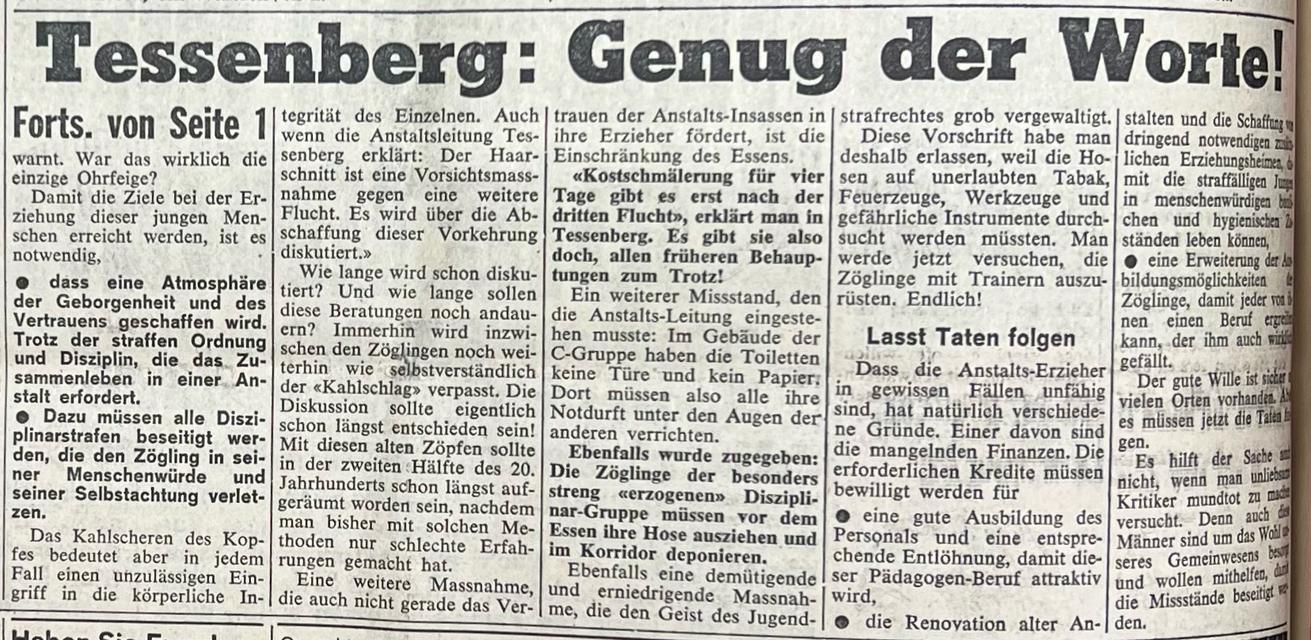

In the mid-1970s, the Swiss daily newspaper “Blick” devoted a two-part series to the question of why adolescents fled from the juvenile correction facility “Tessenberg” in the canton of Bern. Critical reports had already been published in earlier decades. However, they did not lead to fundamental reforms. Before the “Blick” series, the magazines “Sie + Er”, “Beobachter” and “Team” had already reported critically on the conditions in Swiss educational institutions in 1970. This media criticism of the authoritarian upbringing in homes became known as “Home Campaign” and is an expression of the urgency and call for fundamental changes in the home system at that time and was also shown on Swiss TV.

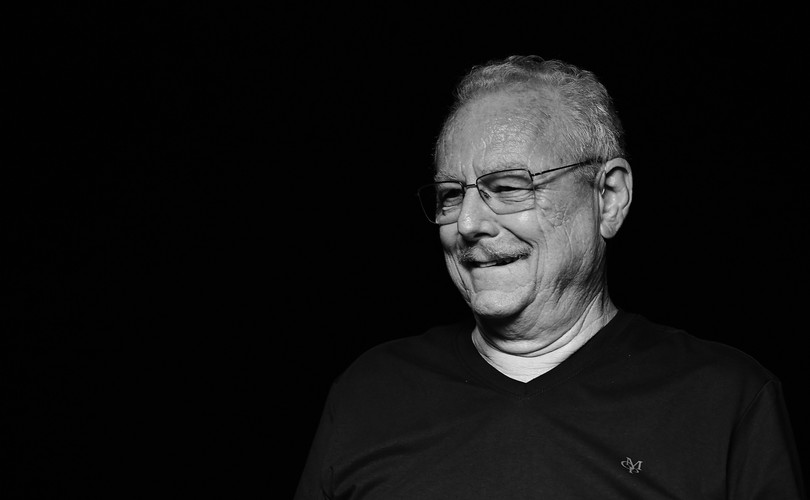

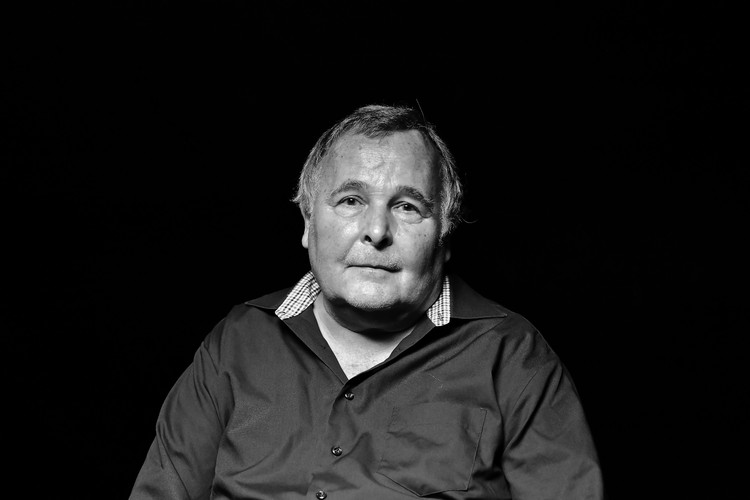

We Talk in this Film

Dependent and Abused

Psychological, physical and sexual violence was part of everyday life for many of those affected by compulsory social measures.

For a long time, corporal punishment was widespread in the upbringing of minors and still is not explicitly forbidden in Switzerland. Indeed, there were early approaches to a non-violent upbringing: individuals or the media repeatedly reported on cases of abuse but in the end the perpetrators were often protected and the victims themselves blamed for the violence they had experienced. Supervision and control, if they existed, failed. ...

Institutionalised Violence

Until after war, physical and psychical violence was an instrument of education and disciplining in homes and institutions. The permitted penal practice was often specified in the regulations and house rules. “Food reduction”, i.e., reducing the food rations, for example, was a common punishment in many homes until the second half of the 20thcentury. Attempts to escape were often punished with savage beatings, prolongation of the internment period and a shaved head as visible sign. This practice changed only during the 1970s.

In addition, many institutions exerted forms of violence that at times bordered on torture. Internees were also verbally humiliated and bedwetters forced into bathtubs with ice cold water. Besides, there is proof of numerous cases of sexual abuse.

The many reports on arbitrariness and abuse show that these weren’t isolated acts of misconducts. They benefitted from the insufficient control structures and a lack of manpower and financial resources. As these structures opened up a large scope of action, the staff had a huge responsibility. Quite a few abused their position of power. This also includes drug trials without consent, which were carried out especially extensively by the director of the Psychiatric Clinic Münsterlingen – despite already existing ethical principles for medical research.

However, at the same time some of those affected had positive experiences in their institutions and foster families and experienced support from supervisors, which also strengthened them for the rest of their lives.

Abuses and Their Consequences

Even before World War One, criticism about the widespread violence and abuses in institutions and homes came up in Switzerland. From the mid 1920s on, the writer Carl Albert Loosli (1877–1959), who himself had grown up in various homes as adolescent, was a fierce critic of the “administrative justice” within the system of “contract children” and institutional homes. Also, in the 1930s and 1940s, several journalistic reports on the living conditions in Lucerne homes or the abuse of a Bernese “contract child” which ended with death, shook up the public. However, it was only in 1970s and within the context of a so-called Home Campaign that the institutions were fundamentally reformed. At the end of the 1970s, the supervision and control of foster care was regulated on a national level for the first time.

Due to the structural shortcomings and the lack of social sensibilisation, the perpetrators had little to be afraid of for a long time. At best, they were admonished or transferred and only in rare cases dismissed. They were practically never prosecuted. Superiors protected them and during the investigations the trustworthiness of the “morally” or “psychically damaged” victims was doubted on regular basis. Out of fear that a statement wasn’t believed, out of shame or because they were pressured, many victims of abuse and sexual abuse remained silent for decades.

Today, the Swiss legislation takes into account the fact, that these victims are often only able to talk about the traumas they have suffered after a long period of time: sexual abuse is no longer subject to a statute of limitations.

Sexual Violence in Court – a Rare Case

In the 1940s, in Bad Knutwil, Lucerne, monks of the local “juvenile correction facility” faced trial. They were accused of sexual abuse of adolescents. However, they were by no means the only perpetrators of this kind, but among the few who had to answer for it in court.

The reports of systematic sexual violence against adolescents in the “juvenile correction facility” in Knutwil by monks and priests in the 1940s were not the only ones. Abuses, and at least one suicide that was connected to them, are also known to have occurred during the following years until the withdrawal of the monks from La Salle 1973. ...

Violence and Sexual Abuse in Knutwil

The “juvenile correction facility St. Georg Wilihof” was opened 1926 in a former health and therapy centre in Knutwil in the canton of Lucerne. Its purpose was the “education of boys aged 12 to18, who are exceptional unruly, morally at risk or in the care of the authorities”. It was run by the “Brothers of the Cristian Schools from Jean-Baptiste de La Salle”. This Catholic order of men was founded 1684 in France and had been active in Switzerland since the mid-18thcentury. The “juvenile correction facility” in Knutwil, where mainly brothers of the German branch of the order worked, was one of two branches in German-speaking Switzerland.

In the early 1930’s, the Communist daily newspaper «Basler Vorwärts» reported for the first time on the “barbaric” educational methods, violence and hunger at the “juvenile correction facility” of Knutwil. The report had been triggered by the death of a boy at the facility. The director of the facility denied the accusations and spoke of “infamous slander”. He received support from the Catholic press which sensed an ideologic motivated “godless propaganda” and questioned the credibility of the victims.

Immediately after the Second World War, two adolescents reported sexual abuses in Knutwil. Their statements were also called into question during the subsequent investigations. Nevertheless, criminal charges were filed. In 1947, two of the school brothers had to answer to the court in Lucerne for “very serious moral offense”. It was mainly for political reasons that they were prosecuted: The church and cantonal authorities wanted to demonstrate to the public that they took their duty of supervision seriously and intervened in the event of allegations of abuse. However, there were justified doubts about this at the time, as it was only thanks to media reports that the inhuman living conditions in the reform school “Sonnenberg” near Kriens (LU) had become known a few months earlier leading to the closure of this home. The criminal charge against the two monks from Knutwil was intended to reassure the public and avoid a second “Sonnenberg” case.

Knutwil Monks in Court – Sexual Abuse Continues

One of the Knutwil monks pleaded guilty in court. He got away with a low sentence, as the court by far didn’t exhaust the already low penalty for sexual abuse. The second monk, however, denied all the allegations, and as the court didn’t believe the statements of the adolescents, he was acquitted due to lack of evidence.

It is not known if the monks continued to work at the Knutwil “juvenile correction facility” after the court ruling. What is certain is that the sexual abuse in Knutwil did not stop after 1947. Two victims, who spent several years in Knutwil from the end of the 1960s onwards, reported that the younger “pupils” were systematically sexually abused. One of the victims at the time took his own life while still in Knutwil. The expert commission “Sexual Assault in Church Settings” recently recognised the sexual abuse in a letter to a victim. How the supervisory authorities at the time reacted to the cases of abuse in Knutwil remains unclear. One victim remembers being questioned. However, in the records of the criminal court of the canton Lucerne there are no indications that a subsequent criminal trial took place.

The cantonal authorities had known about sexual abuse in Knutwil at least since the court ruling of 1947. Since 1942, the Child Protection Commission acted as a supervisory authority for children placed in care, and the “juvenile correction facility” in Knutwil was checked regularly by church bodies. Nevertheless, Catholic monks continued to sexually abuse boys in Knutwil in the following years – because the supervisory mechanisms systematically failed, the statements of the victims were not taken serious and the known abuses were ignored and suppressed as misconducts of individuals.