Everyday Regime

Clear rules determined everyday life in “institutions”, homes, and care places. For a long time, the collective education took precedence over individual needs. Everyday life was focused on work. But there were also other experiences.

Order & Rules

If a person was placed in a home, a “facility” or an institution, they lost their personal freedom.

They had to subordinate themselves to the hierarchic regime of the management and the daily routine it had set. Punishments and privileges ensured order and discipline. In addition, they had to hold their ground in a network of informal rules that prevailed among the internees. ...

More than 1,000 Homes, “Institutions” and Other Facilities

Those affected were placed in foster families or facilities. The cantons, districts, municipalities or private individuals and often also confessional sponsorships were responsible for operation, funding and supervision.

Departure to More Individuality

Since the 1960’s, individual needs were given more weight. The social change favoured this shift.

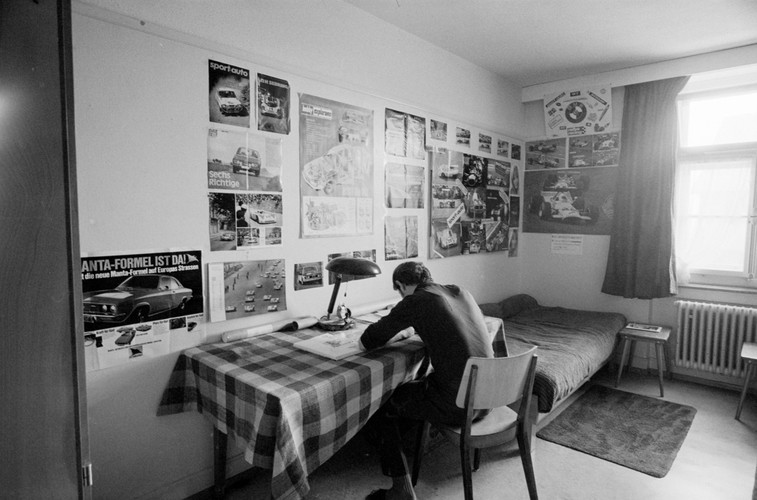

A youth in the “correctional labour facility” Uitikon-Waldegg (ZH) working at his desk (1970). Photographer: Hans Gerber

Since the 1960s, the educational concepts in children’s and youth homes had changed. Training for staff became more differentiated and based more and more on scientific principles. Individual needs and privacy were rated higher. Uniform clothing gradually vanished, girls were also allowed to wear trousers and dorms were turned into private rooms where posters stuck on the walls. The social awakening favoured these changes. Nevertheless, the living conditions in the reformatory institutions were heavily criticised in the so-called Home Campaign at the beginning of the 1970s.

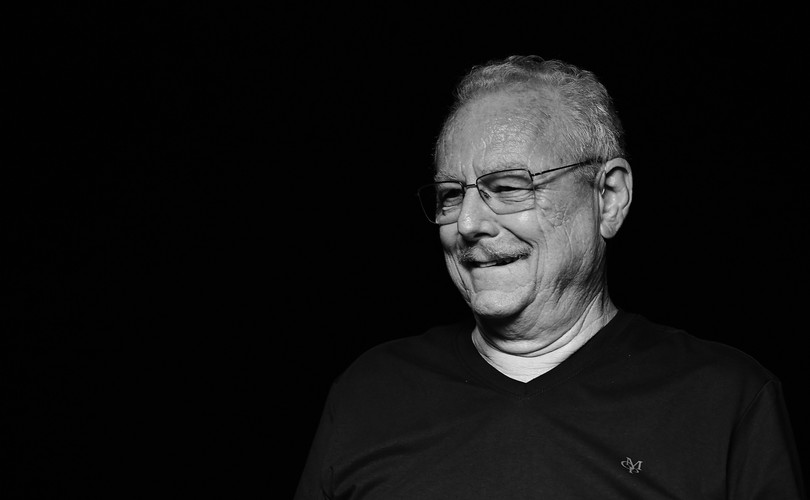

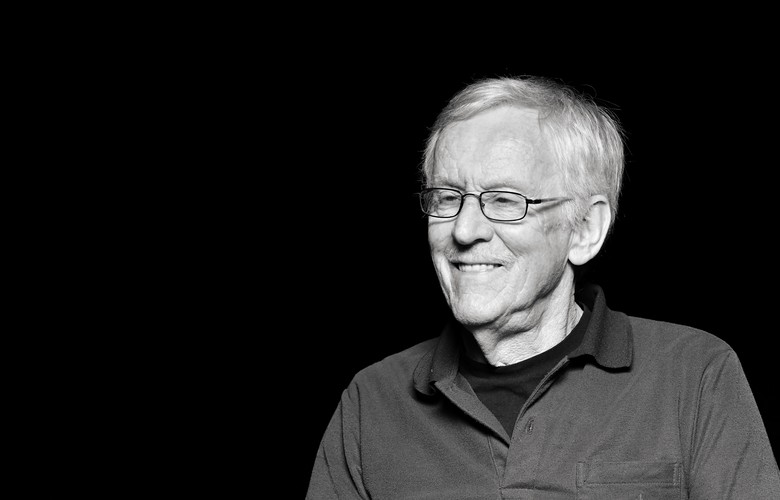

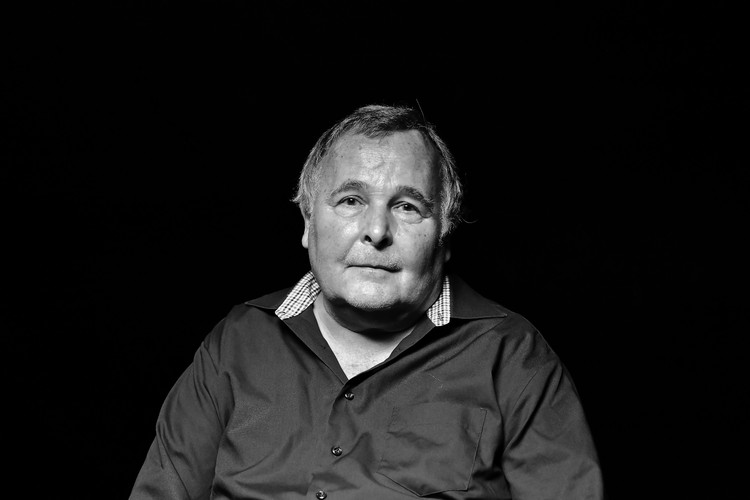

We Talk in this Film

Order & Rules

If a person was placed in a home, a “facility” or an institution, they lost their personal freedom.

They had to subordinate themselves to the hierarchic regime of the management and the daily routine it had set. Punishments and privileges ensured order and discipline. In addition, they had to hold their ground in a network of informal rules that prevailed among the internees. ...

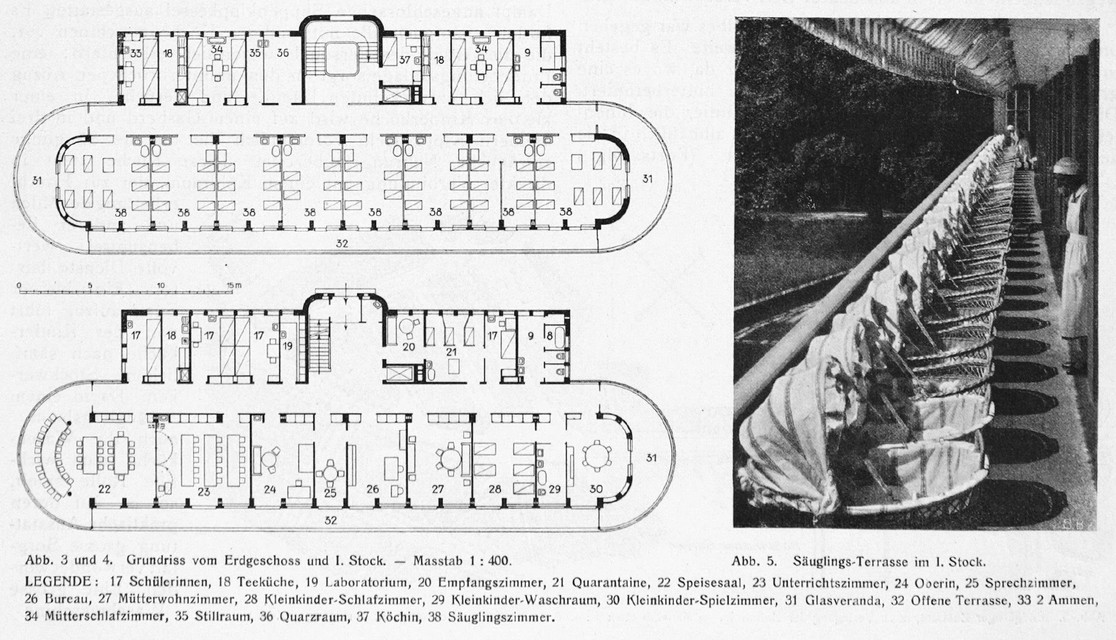

Swiss Residential Care Landscape

In the 19th and 20th century, a diverse residential care landscape developed in Switzerland. More than 1,000 institutions, differing in size and function, were spread all over Switzerland. Their names changed with time and mirrored the zeitgeist. For instance, there were so called orphanages and poorhouses, asylums for inebriates, children’s and youth homes, reformatories, mother-child homes, psychiatric institutions or correctional labour facilities.

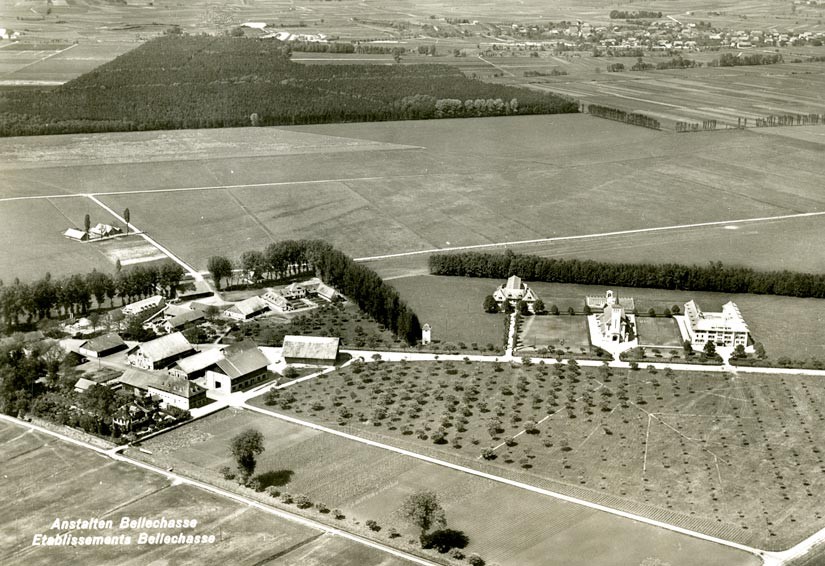

Both governmental agencies and non-governmental associations or religious organisations acted as sponsors of these institutions. Some specialized in one area. Others were multifunctional institutions such as the “Anstalt Bellechasse”, situated in Sugiez (Fribourg) to where both criminal and administrative sentenced men and women were committed to.

In addition to these, there were many specialized institutions such as the Catholic run remedial observation ward “Oberziel” in St. Gallen, where children were psychiatrically assessed and recommendations made. The choice of institutions was large. Because governmental, private and church organisations worked closely together, children, women and men also could be pushed back and forth between institutions and parts of the country.

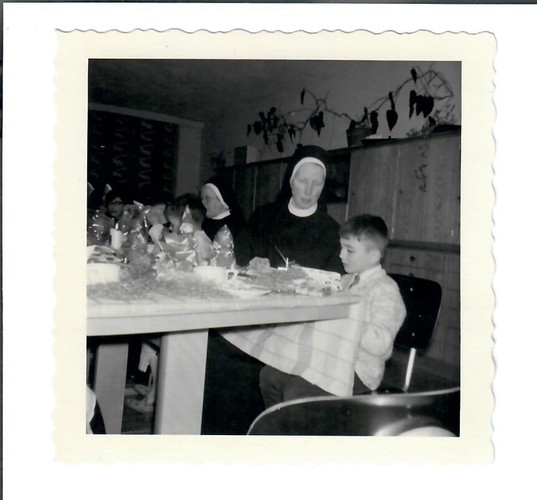

Everyday Life in a Home

A person was placed in an institution according to denomination, sex, age and type of measure. Everyday regime varied depending on which organisation ran it. In religiously run institutions, for instance, the focus was on the “moral-religious” education, so that prayers, masses and church holidays defined everyday life.

What all institutions had in common was that the internees lost their personal freedom and privacy upon entry and had to submit to a hierarchic organisation with the management at the top. The latter maintained order with house rules and disciplinary actions. Resistance, for instance by fleeing, was seriously punished and good behaviour was rewarded with privileges. Furthermore, the internees had their own unwritten rules and hierarchies that defined everyday life. In many establishments cigarettes served as an informal means of payment.

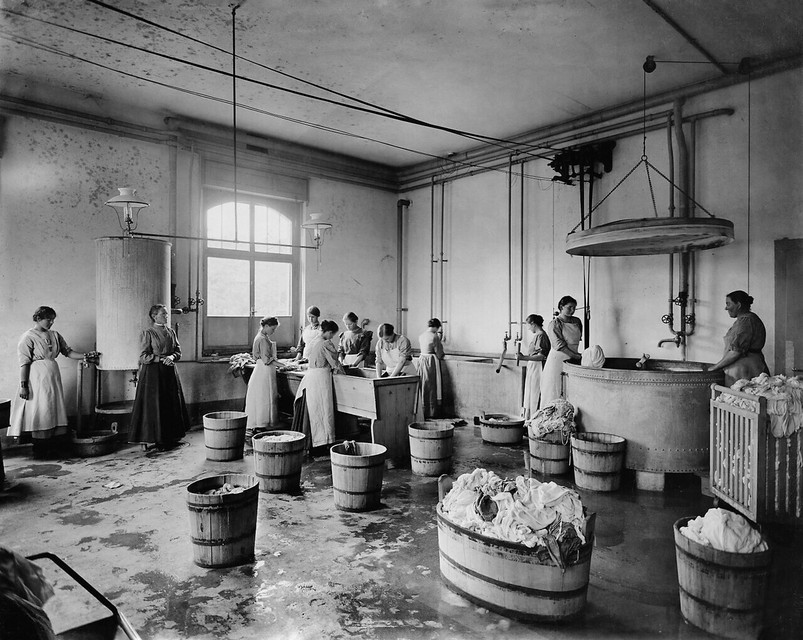

In all establishments, the daily routine was jam-packed, there was hardly any free time, the focus was on work. It served as a disciplinary and regulatory measure and structured everyday life. Moreover, the work of the internees contributed to the funding of the facilities. The employment of women in housekeeping and of men in the affiliated farming operations and craft workshops cemented the bourgeois gender model. This appointed men to paid work outside the house and women to domestic work and persisted well into the 20th century.

Reforms that would have led to break-up the rigid hierarchies, structures and procedures in the homes were long in coming. It was only in the 1960’s and 1970’s and under the influence of a new generation of systematically trained specialists that everyday regimes began to change in favour of the internees. A certain measure of privacy, for example through structural measures, or new oportunities for leisure activities gradually began take hold.