The People Behind the Stories

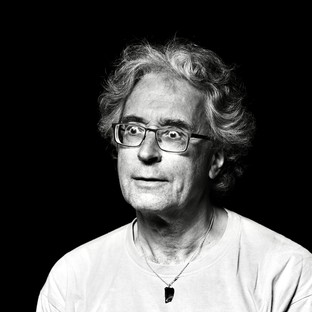

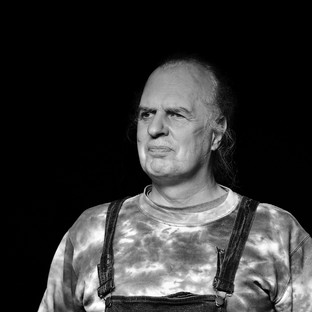

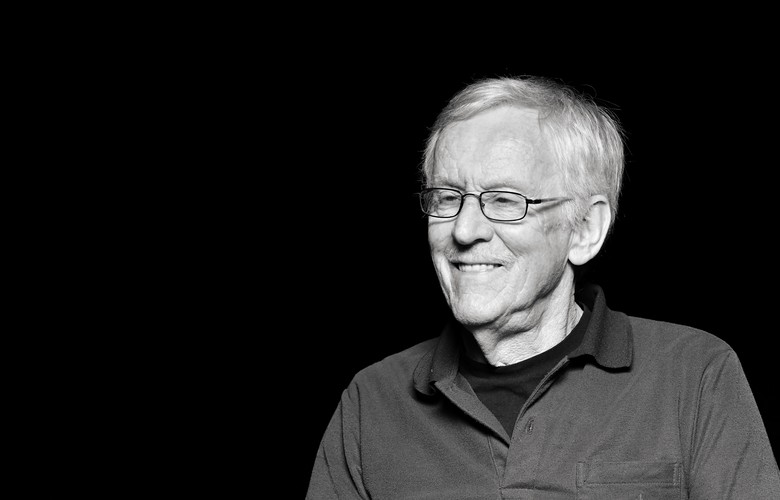

Claude Richstein

“Until I was twelve years old, I lived in a good care place. The horror only began afterwards.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Claude Richstein was born in 1961. His parents could not keep him with them. He was brought to a children’s home and from there to a foster family in Bern who already cared for another foster boy. Here Claude Richstein spent his first years in a loving environment. His foster parents wanted to adopt him, but his biological mother did not give her consent.

At the age of twelve, Claude Rechstein was taken by his guardian to a new foster family in the canton of Valais, as his former foster parents were not prepared to take over the costs for him any longer. A year later he was moved again because his guardian had accused him of stealing cigarettes which was not true. In the children’s home in Aarwangen (AG), where work defined a big part of everyday life, Claude Richstein stayed for the next four years. At the age of 16 he was sent to the ”Pestalozziheim” in Birr (AG). Here he experienced massive violence among the internees for three months. A horror for the youngster.

After his release Claude Richstein lived together with his older foster brother in a shared flat until he was 20. The latter was an important attachment figure for him and a support on his way to a self-determined life for which he was not prepared. Claude Richstein has had many exiting jobs throughout his life and, at the age of 60, has started a new training to become a home carer.

He is grateful for being healthy and having met many people in his life who loved him. He tries to pass on some of this to people who need support today. Claude Richstein draws his strength from his faith; it has helped him to come to terms with what he has experienced and to move on.

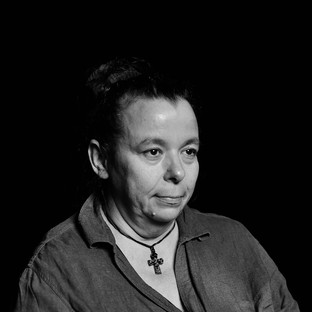

Christina Tomczyk

“My father is my hero and an example for me.”

Photo: Mario Delfino

Christina Tomczyk was born 1974 in Basel. After her parents separated, she initially lived with her mother, until she moved in with her father, Peter Bönzli, as a teenager. Father and daughter had a strong connection from the beginning, and he supported her in all her private and professional ambitions. In 1993, Christina Tomczyk reached the final of the Miss Switzerland pageant. A year later she made her debut as a racing driver at the Swiss Kart championship.

Christina is married to Martin Tomczyk. The couple has two children. After the birth of her children, Christina increasingly asked questions about the childhood of her father. She only knew that the father of her father had died early and that her father and his siblings had therefore grown up in children’s homes. Until then, her father’s stories had only been fragmentary. Not least because the topic had moved into public discussion, the family now talked more and more about the past.

A few years ago, Christina Tomczyk and her father, an uncle and an aunt, visited the children’s homes in Bern where he and his siblings had been cared for as children. She suggested to her father to go public, to talk about his experiences. Also, to show that despite bad experiences in childhood, he has found his place in life and society. And that he has not passed on the experience of neglect, lack of affection, violence and lack of schooling to the next generation.

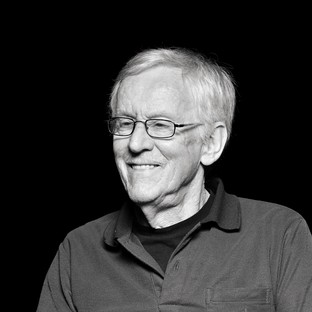

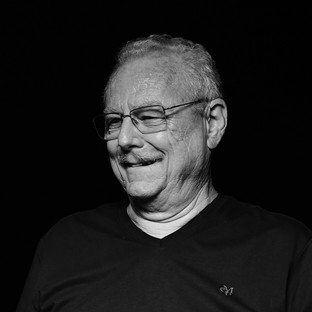

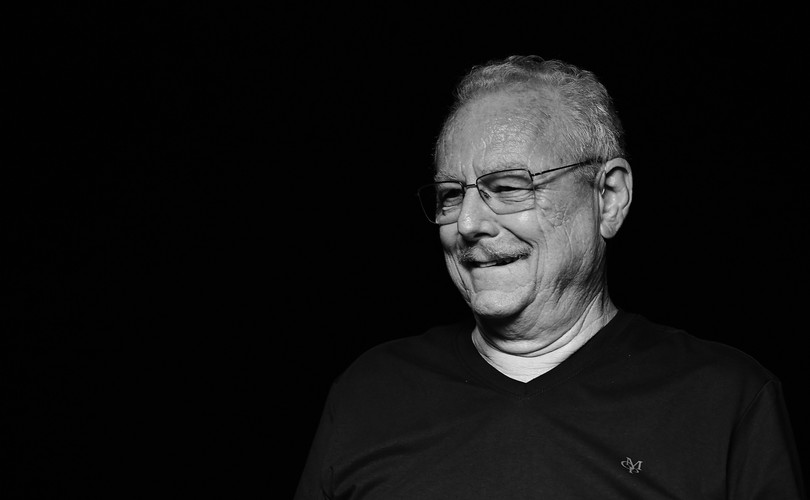

Peter Bönzli

Peter Bönzli talks about:Peter Bönzli

“I have always had people in my life who encouraged and challenged me.”

Photographer: Mario Delfino

Peter Bönzli was born in Bern in 1947. After the death of his father, his mother lost parental authority over her four children. One day, two men took Peter Bönzli away while he was playing in the street and brought him to a transitory children’s home. At the age of five, he was taken to the boys’ reform facility “Brünnen” in Bümpliz.

The first year he spent with the home director’s sons and enjoyed a lot of freedom, but this came to an end when school started: henceforth work had priority and there was little time for school. His younger brother Kurt was placed in the same facility. Together they waited for their mother to visit once a month – often in vain. Sometimes the two brothers saw their sisters, who were placed in the adjacent girls’ home, across the fence.

After finishing school, the boys from “Brünnen” were distributed among various jobs. Peter Bönzli was sent to a postman in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. After a year he moved in with his mother in Basel. He had to cancel a trial apprenticeship as a lab assistant after a work accident in 1964. After that he started to train as a salesman which was difficult for him due to his poor schooling in the facility. His professional career led him from various jobs as a salesman to business consulting. In 1992, Peter Bönzli founded his own company which he sold in 2004 and took early retirement.

Peter (right) und Kurt Bönzli, 2021. Photographer: Mario Delfino

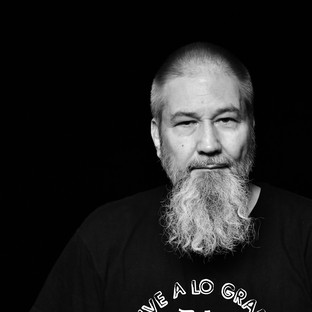

Beni Freudiger

“I have been well taken care of in the children’s home.”

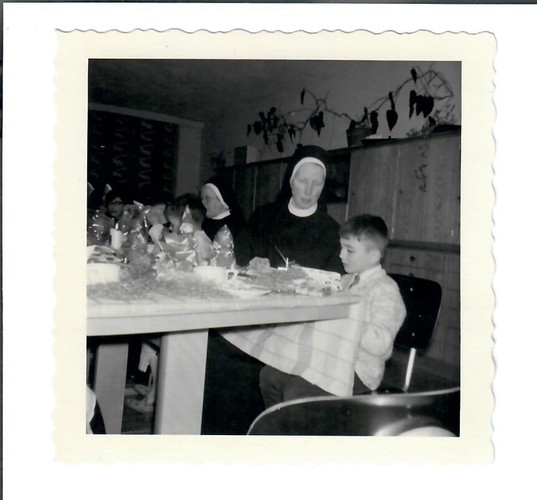

Beni Freudiger was born in 1958 in the canton of Solothurn. When his mother got ill, he and his older brother were sent to the children’s home “Marianum” in Menzingen (ZG) in the summer of 1960. His mother and his father, who lived separately, came to visit sometimes. Upon his entry, Beni Freudiger was the youngest. He stayed at the home for 15 years, until it was closed in 1975.

Beni Freudiger was taken good care of in the “Marianum” and was lovingly looked after by the nuns from Menzingen. He was particularly fond of one of the nuns and she of him.

The Mother Superior, who ran the children’s home Klösterli in Wettingen (AG) after the closure of the “Marianum”, always found ways to give the children special experiences. Christmas, for example, was a celebration of joy, and the way to the room with the gifts was always lit with candles. The approximately 60 children had a regular daily routine and fulfilled small assignments in addition to school. However, there was always enough leisure time. Beni Freudiger, for instance, had his own small garden where he grew vegetables.

Easter 1965: For children who had to stay at the children’s home during Easter holidays, there was an “Easter nest”. Photo: private property

The Mother Superior found a good commercial apprenticeship for Beni Freudiger. After a stay abroad in England, he applied for a job in an accounting firm and later trained as an accountant. Today, Beni Freudiger is the father of three adult children. Despite having been treated with good care at the children’s home, he did not know family life until he became a father himself. He missed this experience later on.

Photographer: Mario Delfino

Since his divorce, Beni Freudiger is often on the road and travels the world. He keeps in touch with a nun who now lives in the motherhouse of the sisterhood in Menzingen. The predominantly negative media coverage of experiences in children’s homes prompted him to go public with his story. For Beni Freudiger it is important to show that there were also other, positive experiences in foster care and that loving care was also possible in the past.

Robert Blaser

Robert Blaser talks about:Robert Blaser

“In my case it concerns three generations.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Robert Blaser was born in Zollikofen (BE) in 1957. To support the family, both parents had to work, so the children were often on their own. In 1962 the authorities confronted the mother with the impossible choice: either stop working or place the children in care. The siblings were torn apart and placed in care. Robert Blaser spent the next ten years in the children’s home Landorf in Köniz (BE). He had to settle quickly into the hierarchy among the boys and later used this to his advantage.

Robert Blaser was always a technophile, but when it came to choosing a career there was no corresponding offer. Because he did not pursue any regular work when he was released at the age of 18, his guardian placed him in administrative care for two years in the forced labour institution “Kalchrain” (TG) as part of a so-called precautionary measure. Robert Blaser remained under protective supervision after reaching the age of 20.

Already Robert Blaser’s father had been placed in administrative care and Robert Blaser’s first wife had not grown up at home either. When she became pregnant, the young couple wanted to marry but did not get permission. One day Robert Blaser’s girlfriend was taken away, and he did not know where she was for a long time. The child was taken from the young mother shortly after birth; it took two years, until the parents had it with them again.

His fascination with technics led Robert Blaser later into the field of insulation. He holds a patent for a Minergie element that is used in housebuilding. Nowadays, Robert Blaser is committed to the concerns of those affected and heads the association “Fremdplatziert”. Together with his partner Brigitta Bühler he has supported more than 100 people applying for a contribution from the solidarity fund.

Brigitta Bühler

“For a long time, I knew nothing about this dark side of Swiss history.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Brigitta Bühler was born in Zurich in 1969. She had a sheltered upbringing and likes to remember her childhood. After completing compulsory education, she did an apprenticeship as a retail saleswoman in a shoe shop. Brigitta Bühler has two children from her first marriage.

Her current partner, Robert Blaser, she met in 2009. Brigitta Bühler only gradually learned about the home placements and administrative detentions her partner had experienced. She herself did not know this aspect of Swiss history. Brigitta Bühler bought books and began to inform herself – which was not always easy for her: the testimonials affected her deeply.

Knowing about Robert Blaser’s story helped her to better understand certain reactions and idiosyncrasies of her partner. Brigitta Bühler supports him in his commitment to the association “Fremdplatziert”, for example in submitting applications for a contribution from the solidarity fund. Again and again, the two of them cannot call or visit the affected persons at home, because they do not want their relatives to know. This makes Brigitta Bühler thoughtful and sad. Therefore, she advises all relatives to listen carefully, to ask and listen again.

Karin Gurtner

“I never solved conflicts with violence if possible.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Karin Gurtner was born in Basel in 1958. Her mother was very young then and unmarried. Her grandparents were officially appointed as her foster parents by the guardianship authority until 1965. The grandparents loved the girl and gave her the foundation that would sustain her throughout her whole life. With her grandfather she spent many hours in the woods, observed and learnt to respect every form of life.

After her mother had married, she suddenly wrenched Karin Gurtner from her grandparents in 1963. The girl would have given anything to be able to stay with them because the visits from her mother had always been marked by coldness and distance. At the age of eleven, Karin Gurtner was placed in the home for difficult girls “Steig” (SH). In 1975, five placements followed in within a few months, including a stay in prison and then in the Psychiatric Clinic Breitenau (SH), because the authorities did not know where else to put the youth.

At the end of 1975, she was put into administrative detention in the juvenile correction facility “Lärchenheim” in Lutzenberg (AR.) Here the hierarchies among each other were very pronounced. Karin Gurtner gained influence but never used it to her advantage, instead she managed to protect other young people.

Karin Gurtner did not allow herself to be forecd into bourgeoise gender roles. She wanted to go her own way and did training time in electronic design. Later she trained as a beautician and makeup artist and opened her own business. Her mother did not leave her alone even as an adult and made sure customers stayed away. The family dispute continued over the inheritance with Karin Gurtner being accused of having plundered the inheritance of her grandmother, even though she had no access to it.

Karin Gurtner is a fighter. She draws strength from the tree of life Yggdrasil and from a motto of the old norse gods: “Get up and keep fighting!”

1979

Nadine Felix

Nadine Felix talks about:Nadine Felix

“Look, ask, engage: this is just as important today as it would have been then.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Nadine Felix was born in Zurich in 1975. Her mother was an alcoholic and she only survived as a baby because her two older half siblings took care of her. Soon after her birth, she was adopted by a couple. Nadine Felix only found out what had happened then at the age of 35, when she met her birth family. Until she was 14 years old, she believed she was growing up with her biological parents. When her adoptive parents separated, Nadine Felix was suddenly placed in care, completely unprepared and in the middle of 5th grade. After a time in Chur (GR), she was taken to the “Heim Hirslanden” (ZH) at the age of 14. In a letter from the Chur guardianship authority, she learned that she had been adopted as an infant.

Sometimes, Nadine Felix and her colleagues from the facility were allowed to go out, went to parties and danced the night away. Nadine Felix has kept the shoes she wore then to this day. For a housekeeping year Nadine Felix was to be taken to a closed educational facility. Together with her boyfriend she planned to escape to Italy – unsuccessfully: in handcuffs she was taken to the closed ward of the “Loryheim” (BE). Nadine Felix has never been involved in decision-making processes. She was never asked about her needs, despite having met numerous experts and having been in various therapeutic settings.

When her guardian died, Nadine Felix was released from guardianship at the age of barely 20. She was not supported in the transition to an autonomous life and slipped into drug addiction. After seven years of heroin use, she opted to go to rehab. A year later, her now adult son was born, whom she raised on her own. Nadine Felix completed various trainings, most recently as an educational nursery manager. She managed a nursery for ten years. To treat everybody with respect is important to her – and it is just as important to her to talk about it when this not the case.

Foto: Mario Delfino

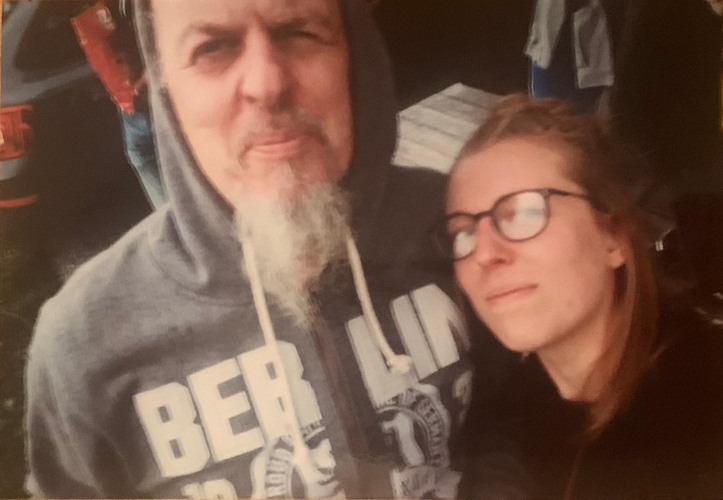

Kurt Bönzli

“The fact that my brother and I have contact again today is important to me.”

Photo: Mario Delfino

Kurt Bönzli was born in 1949 in Bern. When his father died, his mother lost parental authority over her four children. Subsequently, all of them were placed in care. Kurt Bönzli, together with one sister, was sent to Beatenberg for a cure and then sent for a short time to a girl’s home where his sisters were also staying. After that Kurt Bönzli spent the years from 1957 to 1966 in the boys’ reform facility Brünnen in Bern-Bümpliz. His older brother, Peter Bönzli, was also placed in this facility.

Here, work was the priority, schooling was neglected. A hard drill prevailed, the boys were beaten and self-determination was an alien concept. Sometimes Kurt took refuge in a hut made from woollen blankets and withdrew for short moments. His sisters lived in the nearby girl’s home – sometimes he could give them a wave across the fence.

At the end of their schooling the boys from “Brünnen” usually were distributed among various jobs. Kurt Bönzli wanted to decide for himself about his education and was finally able to start an apprenticeship as a cook in the city of Bern.

At the age of 20, he was released from guardianship. Kurt Bönzli enjoyed his freedom and was on the road a lot. Cooks were sought after, so he could change his job anytime and find a new one. What he did not want was to be responsible for others. That is why he didn’t want children.

During this time, he had hardly any contact with his siblings. After a heart attack, he decided to change his life. He drank less alcohol and sought contact with his older brother, Peter Bönzli. The relationship is important to him, the two see each other regularly.

Kurt (left) und Peter Bönzli, 2021. Photo: Mario Delfino

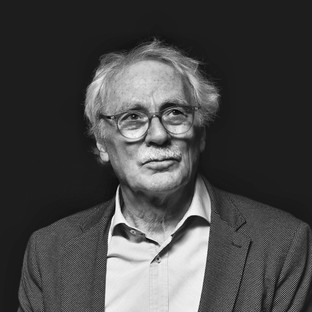

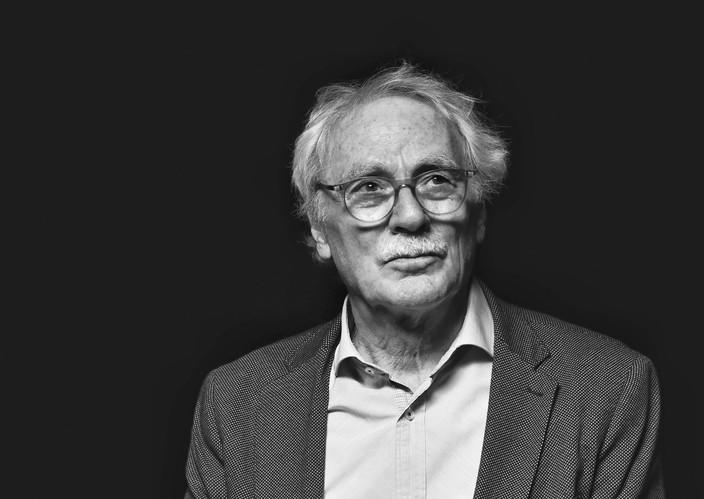

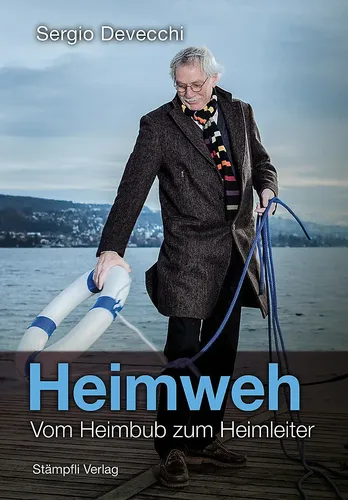

Sergio Devecchi

Sergio Devecchi talks about:Sergio Devecchi

“Out of shame, I remained silent for a long time and then opted for a reassessment.”

Photo: Mario Delfino

10 days after his birth in 1947, Sergio Devecchi was placed in the Protestant children’s home in Pura in the canton of Ticino. Prayer, labour and obedience accompanied him throughout his childhood. After 12 years, he was suddenly sent to another children’s home. He escaped several times and tried to return to Pura by foot. Finally, his guardian transferred him to the children’s home “Gott hilft” in Zizers in the canton of Grisons. Shortly after confirmation, he was brought back to Ticino, again without being informed in advance, by a hitherto unknown uncle.

Here, Sergio Devecchi started a commercial apprenticeship and lived in a room in Lugano at the age of 17 without any support from the authorities. He was lonely and suffered hunger again and again. With the support of private individuals and the “Young Men’s Association” things were looking up. In 1969, Sergio Devecchi began to study in Basel to be a social education. He then worked as educator and home director in various institutions in Ticino and the German-speaking part of Switzerland and was, among other things, president of the Professional Association for Social Education and Special Needs Education (Integras).

Out of shame, Sergio Devecchi disclosed his growing up in facilities only after he was retired. He still is active as a consultant in his former field of work and committed to the socio-political reassessment of compulsory social measures and placements.

Sergio Devecchi has compiled his experiences in the highly respected book “Homesickness. From home boy to home director”. (Stämpfli Verlag 2017).

Gabriela Pereira

“We children were rendered stateless and our family was torn apart.”

Photo: Mario Delfino

Gabriela Pereira was born in 1964 in Wohlen in the canton of Aargau. Her mother was from Portugal, her father was Swiss. The parents planned to marry. Nevertheless, at the age of 18 months, Gabriela Pereira was placed in an orphanage that was led by nuns from Menzingen. By the time Gabriela Pereira reached the age of 17, a foster family and three Catholic institutions had followed. During the time she spent at the Protestant “home for difficult children” in Freienstein (ZH), she was, like many other institutionalised children, hired out to farmers during the holidays. In all places Gabriela Pereira experienced violence and repeatedly sexual abuse.

When Gabriela Pereira’s father died in 1967, the social authorities denied her access to the inheritance and the money he had deposited as security for the children. Because Gabriela Pereira and her brother had been rendered stateless and lacked the financial means, a departure to Portugal was impossible. It only was when she was a teenager that she was granted a Swiss passport. Only thanks to her mother, who always managed to bring her daughter back home and to wrap the bad experiences into stories with humour, Gabriela Pereira managed to retain her inner liveliness to this day.

After the death of her mother (2003), Gabriel Pereira intensified her personal reassessment and became politically involved. “As long as survivors are left alone with the results of traumatisation, have hardly any financial means to ease consequential health damages and continue to be exposed to administrative coercive measures, there is no reassessment for the survivors,” says Gabriela Pereira.

Gabriela Pereira: giving expression to the shattering and at the same time to the resistance (oil on canvas, 2020). Photo: private

Rita Brunner

Rita Brunner talks about:Rita Brunner

“There is always a balance in life. One cannot take without also giving.” (Menuhin)

Photo: Mario Delfino

Rita Brunner was born in 1966 in Zurich. She never really knew her father, and her mother was overwhelmed with the two daughters. At the age of 6 weeks, Rita Brunner was taken to a nurse’s home in Zurich and later, together with her older sister, to a private children’s home in Ossingen. The home was closed because the operators allegedly belonged to a cult.

Under the pretext of going on an excursion, the two girls were taken to the “Kinderdörfli Rathausen” (LU). Rita Brunner was three and half years at the time and spent the next 12 years there. She had good and bad experiences in the facility, always depending on the actual educators. In addition to collective punishment, she also experienced psychological and physical violence. Hunger, fear and loneliness often accompanied her, especially in the evenings.

After completing her compulsory schooling, Rita was released at the age of 15 and placed in a position as a groom. The path to an independent life was not easy for Rita Brunner. During this time, she often thought of suicide. Then, for the first time, she met a person who wanted to know who she was and what she had experienced, who listened to her and whom she could trust. In her mid-20’s, Rita Brunner made a conscious decision for life.

On her way she met time and again people who encouraged her and supported her, professionally as well as privately. In the beginning Rita Brunner didn’t want to have a family on her own because she did not want to put anyone at risk of maybe having to live a life like she had. Meanwhile she is married nevertheless and has a grown-up son. Her husband refers to her as their tower of strength.

Today Rita Brunner is a local councillor and in her work she tries to change things positively in small ways. In particular, she tries to avoid that people who are in need of support today are violated in their integrity: she pays special attention to old-age and nursing homes.

Bruno Frick

“Reliable relationships are central to the development of children and adolescents.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Bruno Frick was born in 1957 as the oldest of three brothers and grew up with his family on the lake of Zurich. He first encountered children living in the Wädenswil orphanage as a Scout Leader. When the orphanage closed, and the children and youths were distributed to other places, a 14-year-old did not want to go to another facility. She asked Bruno Frick if she could live with him and his flatmates. The competent authority granted the request and appointed him as foster father, later as guardian.

In 1978, Bruno Frick began studying to become a social and special educator. For his final thesis he interviewed many former residents of the Wädenswil (ZH) orphanage. This work and his studies caused him to think more critically about society, and he came to the conclusion that constant relationships are central to the development of children and adolescents. He has always been guided by this, as the educational manager of the “Jugendsiedlung Utenberg”, as a foster father and later as a father of his own children. Since the 1990s, Bruno Frick has offered integration support, mainly to young adults aged 18 and over who left the home where he worked. At the same time, he ran a socio-educational foster family together with his wife. Six foster children lived between four and 18 years in his family.

As a member of the board of trustees of the Guido Fluri Foundation, Bruno Frick has been committed since 2014 to the concerns of those affected by compulsory social measures and placements in care and to a broad social discussion of this topic.

Jasmin Schweizer*

“Every child has the right to education.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Jasmin Schweizer* was born in the city of Zurich in 1957. Her parents and the whole family were looking forward to the family addition. Jasmin Schweizer was often ill, fought against infections and often had to go to the children’s hospital. Thus, she missed out on subject material in school and therefore found it increasingly difficult to follow the lessons. At the age of 14, Jasmin Schweizer was taken to a home in the Romandie for the first time. A year later she was taken to the Rudolf Steiner home “Montolieux” above Montreux (VD) where children of influential parents also lived. After an attempted sexual attack, the teenager fled. Another placement in a Protestant daughters institute in Lucens followed.

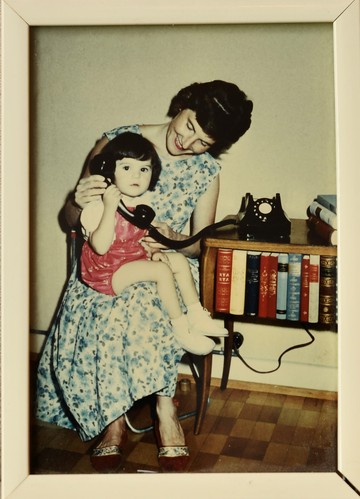

Jasmin Schweizer* in the living room with her mother, circa 1959. Photo: private

Jasmin Schweizer’s lack of schooling made it difficult to find an apprenticeship. In 1975 she began an apprenticeship as a nurse’s aide at the Cantonal Hospital Münsterlingen. The student nurses were housed in the nurses’ home of the nearby psychiatric clinic, where Jasmin Schweizer was forced to take pills with strong side effects. The extensive test series were carried out under the responsibility of the head physician Roland Kuhn – without the consent of the persons tested and despite the already existing ethical principles regarding medical research on humans. When Jasmin Schweizer refused to take the medication, the head physician threatened her with compulsory institutionalisation. Her father took the young woman home.

Henceforth, numerous health setbacks made her professional life difficult. Jasmin Schweizer is also affected by the disease endometriosis. To support other persons affected, she has founded a self-help group. She continued her own education and has found a way to deal with the experiences she has had, even though it still is a struggle.

*The name was replaced by a pseudonym.

Tanja Meier*

“Already my mother and my grandmother did not grow up at home.”

Photo: Mario Delfino

Tanja Meier was born in1965 in a region called Zurich Oberland. The mother was only 18 years old and not married when her first child, Tanja Meier’s brother, was born. A year later the daughter was born. Tanja Meier’s father came from Sardinia. At eleven months, she was placed in a foster family that was a member of a pietistic free church and stayed there until she was 25 years old. Her brother was pushed from one place to another.

In comparison to her brother’s childhood, she had fared well, says Tanja Meier. But her foster mother took her aggressions out on her and constantly devalued Tanja’s mother and grandmother. This influenced the girl: she didn’t want to become like her mother. Tanja Meier and her brother were not the first in their family not to grow up at home – her mother, her mother’s siblings as well as her grandmother had already been placed in care after the death of one of the parents. Tanja saw her biological father only on visiting Sundays. On these occasions he molested her and when she did not want to visit him anymore, her guardian threatened to send her to a children’s home.

When Tanja suffered a breakdown at the age of 16, the foster parents declined the support of an educational psychologist. It was not until 2017, that Tanja knew why her health still was poor at times: she suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. As an adult Tanja Meier also experienced psychological violence in her marriage. The father of her daughter tried, among other things, to deprive her of her child. After another breakdown in 2004, she found the strength to leave her marriage in 2007 and to build a new life together with her daughter.

*The name was replaced by a pseudonym.

Tanja Meier* with her daughter Julia*. Photographer: Mario Delfino

Julia Meier*

“Relationships at eye level and with respect are important to me, and they are possible.”

Photo: Mario Delfino

Julia Meier* was born in 2001. Her mother grew up with a foster family in Switzerland, her father is from Cuba. When her parents separated, Julia was 5 years old. Before that she had witnessed her parents’ relationship problems: when they argued, she was in her room and heard everything. Julia visited her father regularly until she was ten years old. Then she broke off the contact, because her father pressured her again and again and was never pleased with her.

The first years after the separation of her parents were not easy for Julia. She was dyslexic and her school performances depended heavily on her wellbeing. After her mother’s break down which had led to the separation from Julia’s father and after the subsequent divorce it took time for the mother to regain the capacity and enough strength to respond to her daughter’s needs. During this time professional psychological support from specialists was important for Julia Meier. In the years that followed, mother and daughter found a common path and Julia Meier was able to express her needs better and better. Today she has a good and close relationship with her mother, and they can discuss the experiences in their family that span the generations together.

*The name was replaced by a pseudonym.

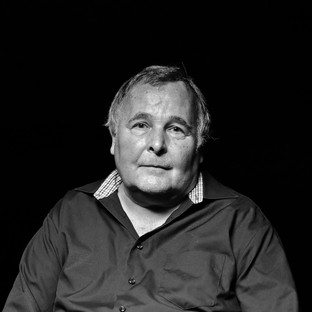

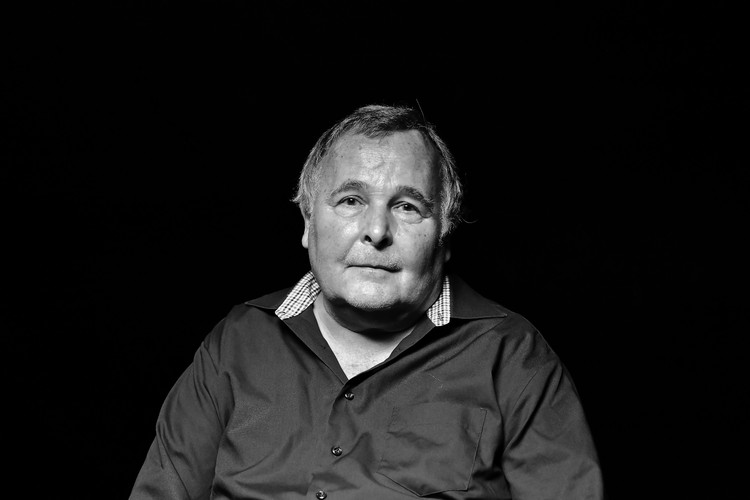

Mario Delfino

Mario Delfino talks about:Mario Delfino

“I am fine – if it weren’t for these stories.”

Foto: Christian Witschi

Mario Delfino was born in Italy in 1955. For the first five years he grew up in an orphanage in Bergamo, where he had a loving carer. Then he was adopted by a Swiss couple and brought to their home in Thalwil (ZH). Here he wasn’t fine: he was often locked up and beaten. Finally, his adoptive mother brought the boy to a children’s home in Altdorf (UR). Mario Delfino experienced the time there as strongly marked by religion but not by violence. After four years, the nuns from Menzingen sent the boy back to Thalwil to his adoptive parents.

At the age of 12, Mario Delfino and two school mates stole a cash box. They found 40,000 Swiss francs in it but returned it to owner by post. A few days later, Mario Delfino was arrested in the schoolyard and taken away in handcuffs. The next four years he spent in the “juvenile reform facility” in Knutwil (LU). The home was run by German monks who inflicted massive physical and sexual violence on Mario Delfino and other boys.

In 1972, when he was 16, Mario Delfino was released from the facility. But his adoptive mother no longer wanted him with her and called the police. The youngster had to wait for three weeks in a detention cell in Horgen (ZH) until the juvenile attorney took time for him. It had been him who had committed Mario Delfino to Knutwil back then and now he envisaged another administrative detention. But when a social worker joined the conversation, Mario Delfino experienced for the first time that someone took time to listen to his story. The social worker took him to her home and found him a job.

Later he moved to Zurich. With the help of Ernst Sieber, a priest for the homeless in Zurich, he found stability in life. Together with his wife Katharina Delfino, he worked as a caretaker in a school in Zurich for 18 years. He is father of two adult sons. Mario Delfino is member of the project team “Our faces – Our stories”.

At a private audience in 2019, Mario Delfino spoke to Pope Francis and told him that he was watching closely how the Catholic church dealt with the sexual abuses in its own ranks.

Andreas Jost

“The thirst for justice drives me. That we do not achieve it makes me angry.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Andreas Jost was born in 1961 in Basel. When his parents divorced, his mother was given custody. She was violent and regularly humiliated the boy. As a result, the guardianship authority placed him in a children’s home and later in two foster families and in many more homes. Finally, he ended up in a juvenile prison without having committed a crime. During this time, Andreas Jost had nobody who met him at eye level, supported him and set an example in empathy. As time went by, he didn’t put up with anything and did not shy away from confrontation with his guardians.

At the age of 15, Andreas Jost was left to fend for himself. He went to Bern, where he was homeless for some time and kept taking on new jobs. Not knowing about the value of education back then, he did not do an apprenticeship. The constant change of schools meant that Andreas Jost was unable to follow a career path according to his abilities. He was more and more troubled by psychological problems: the abuses and traumas of his childhood caught up with him so that, in his mid 20s, he could no longer work and applied for disability pension. Always living on the breadline restricted his life and made social contacts difficult. To this day, he suffers from nightmares and feels the long-term health effects of the abuses.

Andreas Jost was a member of the “Round Table for Victims of Compulsory Social Measures and Placements”. Moreover, he is not afraid to call a spade a spade. He is especially committed to improve the present living situation of those affected, e.g., with a lifelong pension.

Heidi Lienberger

“We still feel the consequences of his childhood in everyday life.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Heidi Lienberger was born in Liestal (BL) in 1958. As the youngest of five children, she grew up well looked-after. When she left home at the age of 18, she was confronted with the world for the first time. Her first husband supported her in finding her way in life. She took on various jobs and today works as a waitress. In earlier years, Heidi Lienberg was very creative and sometimes sold handmade items at a market. Her current partner, Andreas Jost, she met 21 years ago. He addresses things directly, which not everyone likes. It is precisely this open and direct manner that Heidi Lienberg appreciates about Andreas Jost, at least most of the time. She herself is rather reserved.

Her partner has told her about the abuses and the injustice he suffered in his childhood and youth and wrote it all down for her. They talked about it a lot. To Heidi Lienberger it is incomprehensible, how people can treat their wards this way.

They both still feel the consequences in everyday life. An untreated bronchitis in his childhood torments her partner with coughing fits. Nightmares und insomnia keep him from rest at night. More recently, epileptic seizures have been added to the mix which increasingly frightens Heidi Lienberg. In addition, financial restrictions make a self-determined life and social contacts impossible. All of this puts a heavy strain on their relationship and only recently almost caused it to break up.

Heidi Lienberger strongly supports her partner in his commitment to the reassessment of compulsory social measures and placements. She admires his perseverance and his energy for this work.

MarieLies Birchler

MarieLies Birchler talks about:MarieLies Birchler

“Sometimes I lack the words.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

MarieLies Birchler was born in Zurich in 1950, the first of five siblings. In 1951, the authorities brought her and her younger brother to the orphanage in their home community Einsiedeln (SZ). Both children were undernourished, sick and neglected. In this orphanage an eleven-year ordeal of violence and fear under the regime of the nuns from Ingenbohl started for MarieLies Bircher.

As a bedwetter and with her bright nature, she had a particularly hard time. She was pushed under water, beaten up badly, locked in the attic for days. Exposures, humiliations, insults and the accusation of being possessed by the devil dominated her everyday life. As she grew older, MarieLies Birchler started to fight back, until, at the age of 13, her guardian picked her up and took her to the reform school “Burg” in Rebstein (SG). There she got better. However, it was only at the reform school “Waldburg” in St. Gallen, where she was sent to in 1968, that she was able to build up trust to an educator for the first time.

At the age of 20, MarieLies Birchler was released from guardianship. She trained to become a psychiatric nurse and later worked in leading functions. In 1978, her brother Hanspeter committed suicide, a heavy blow for the young women. MarieLies Birchler kept silent about her childhood for the most part until her numerous traumas caught up with her and made her ill. She suffered several breakdowns, could no longer work and had to apply for a disability pension.

When she was better again, she supported families and their children and continues to do so to this day. MarieLies Birchler has also been involved for several years in the reassessment of compulsory social measures. She does this for all those who cannot or no longer can speak for themselves. She is part of the project team “Our faces – Our stories”.

July 1978

Annemarie Iten-Kälin

Annemarie Iten-Kälin talks about:Annemarie Iten-Kälin

“It is time that the history of the orphanage in Einsiedeln is also investigated.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Annemarie Iten-Kälin was born in 1956 in Willerzell (SZ) as the eighth child of the Kälin family. When she was between seven and eight years old, she lost both parents in quick succession: the mother died of a serious illness and the father committed suicide half a year later. The family was ripped apart, for the oldest ones jobs were found or they were rented out for work and the four younger ones were placed in the orphanage in Einsiedeln. This was initially run by nuns from Ingenbohl. At the end of the 1960s, the management changed and a male home director took over.

The hope that there would be more space for joie de vivre lasted only a short time. Admittedly, the children received toys and there was more free time. But the home director also punished arbitrarily and with violence. Furthermore, he committed sexual assaults for which he was never prosecuted. When the situation in the orphanage became known through a letter from Annemarie Iten-Kälin and a supervisor was to be appointed, the home director couple resigned. They blamed her and her sister for this.

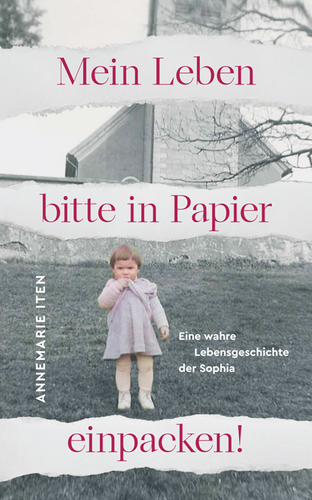

Annemarie Iten-Kälin had to complete an internship to become a kindergarten teacher. At the children’s home “Klösterli” in Wettingen (AG) she witnessed a loving relationship with the children which showed her that things could be different – even then. During her education at the Seminar in Menzingen, Annemarie Iten-Kälin met her future husband. She then moved back to Einsiedeln, and they started a family. When her daughter got sick, Annemarie Iten-Kälin and her husband with son Michael accompanied her until she died. She recorded her daughter’s life and death in the book “Stefanie, ein Engel auf Erden”.

Published in 2023.

Now her second book is almost completed. It is her story which stands for many others. Annemare Iten-Kälin fights persistently for justice, also for the history of Einsiedeln’s orphanage to be reassessed. The political decision to do so was taken in summer 2022.

Alois Kappeler

“It was not a nice life.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Alois Kappeler was born in 1953 in Galgenen in the canton of Schwyz, the 13th of 14 children. Two days after his birth he was taken away from his Yenish parents, who lived in a caravan, and taken to a children’s home in Solothurn that was run by the “Seraphisches Liebeswerk”. In the following 18 years, Alois Kappeler was moved again and again – in total he was in far more than 20 different facilities and care places. There he experienced physical and sexual violence again and again.

When Alois Kappeler was of age, he wanted to be released from guardianship, but his guardian opposed it. In his early 20’s, he left his job one day and hid for eight years on an alp in the canton of Grison. After an accident in which he suffered severe head injuries, his guardian found out where he was staying.

Alois Kappeler was admitted to the Cantonal Psychiatric Clinic St. Urban (LU) and four years later transferred to the Psychiatric Clinic Beverin (GR). There he was to be castrated against his will because he was attributed an excessive sex drive. In this context he injured a guard and was moved to the prison Realta (GR). The journalist Hans Caprez from the “Beobachter” made sure he was released and made his story public.

In 1994, Alois Kappeler met his wife Eva through an advertisement in the magazine “Tierwelt”. She became his most important support. Initially he moved in with her in Davos, later they moved together to Wiesen, a village within the municipality of Davos. A day after Alois Kappeler had inquired about work at the municipality, a representative of the authorities was at their door: The couple was placed under guardianship. With legal support, they were only able to free themselves from this in 2004, thus 6 years later.

Anton Aebischer

Anton Aebischer talks about:Anton Aebischer

“This smile has protected me and led me through life. It does not show how much unspeakable suffering is hidden behind it due the arbitrary behaviour of officials in those days!”

1951 ...

Born: 21st July 1948, Aarau

Hometown: Guggisberg (BE)

I have made it and am an independent person, citizen of this state, “home country” (“landscape of institutions”)! I got nothing from the state. I had to work hard for everything on my own. On the contrary: the state gave me a hell of a start in life! My youth was stolen from me in the facilities. With defamatory “expert reports” (Oberziel, St. Gallen), which still hurt today, with mental separations from the rest, the “normal” society, from so-called experts, luminaries at the time!

I was discharged from the army with “the best of thanks for the rendered services” as a private with an officer’s function in my last service! Moreover, with additional voluntary services in the army, without credit, I also served the state. Of course, I have had various professional jobs, also for a longer time, where I was made redundant for economic reasons. I took the opportunity to buy into the pension fund with a three-digit amount, so that today I am not dependent on the state, unlike many. I am a full taxpayer! I do not have to thank anyone!

2021 ...

Uschi Waser

Uschi Waser talks about:Uschi Waser

“My life was good until the day I read my files.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Uschi Waser was born in 1952 in the canton of Zurich. At the time of her birth, her mother was unmarried. Because of her Yenish origins, Uschi was placed in care and under guardianship. In the first 13 years of her life, she was placed in 26 different places. After having been abused for years by her stepfather, Uschi Waser was raped by her uncle on the night of her 14th birthday and subsequently placed in administrative detention in the Catholic institution “Zum guten Hirten” in Altstätten in the canton of St. Gallen.

After her release, Uschi Waser founded a family and after her divorce cared alone for her daughters. When she inspected the files, she learned that the assessment from her guardianship files had been interpreted exclusively to her disadvantage in the lawsuit against her stepfather and uncle. Her life was never the same after the inspection of the files.

Text: Uschi Waser, presented at the "Round Table for the Reappraisal of Forced Measures and Placements before 1981", 2014.

For many years, Uschi Waser has been committed to reassessing administrative coercive measures and placements as well as the role of the judiciary in this context. She was the representative of the victims of Pro Juventute at the “Round Table on Compulsory Social Measures and Placements Prior to 1981” (2013-2018) and has chaired the “Naschet Jenische” foundation since the 1990s. In 2022, Uschi Waser received the Somazzi Prize. It is awarded annually to a woman or group of women who fight for education, women’s rights and peace.

Afra Flepp

“You can accomplish a lot with very little if it comes from the heart.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Afra Flepp was born in Zurich in 1947. During her childhood she was repeatedly placed in homes and foster families. First in the canton of Ticino, where she experienced a regime of award and punishment. A short stay at home was followed by a placement in a foster family in the Zurich Oberland. The farmers took the child in because of the board money. After her foster brothers had spied on her in the toilet, Afra Flepp was transferred once again, this time to the Pestalozzi home of the city of Zurich in Redlikon-Stäfa. As one of few she was allowed to attend the public school in the village and sometimes smuggled sweets into the home. For the last part of her compulsory schooling, Afra Flepp was once again placed in a foster family.

While still an apprentice graphic designer, Afra Flepp moved into an own room and became self-employed after her graduation; which was far from obvious for a woman in the 1970s. Until her retirement, Afra Flepp worked in her studio in the city of Zurich which soon became a meeting place for the youth of the neighbourhood. They liked to drop by at Afra Flepp’s, as hardly anything was forbidden and there was a lot to discover.

Afra Flepp first attracted attention as an artist in 1975. The facade painting with clouds and rainbow at the Kreuzplatz in the city of Zurich was talked about. Today she paints precise works of art using a special acrylic spray technique.

Endlos 4neu, 2022

Eva Kappeler

“He didn’t know fondue and raclette – they never had that in the facilities.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Eva Kappeler was born in Davos in 1954. She grew up with seven siblings in a loving family. Her first husband died early (1987), and so she was left alone with her three children. For a year she also ran the family farm on her own. When she got ill due to blood poisoning, the guardianship authorities wanted to take the children away from her. With the support from her family doctor, Eva Kappeler was able to go on holiday for four weeks and to recover. The family stayed together.

Her second husband, Alois Kappeler, Eva Kappeler met through an advertisement in the magazine “Tierwelt”. When she saw him, she knew they belonged together. That was in 1994. After their marriage they moved from Davos to Wiesen, where Alois Kappeler inquired at the municipality about work. He was turned away and the following day a representative of the authorities was at the door: Alois and Eva Kappeler were placed under guardianship which was only dissolved six years later with the help of a lawyer. During this time Eva Kappeler lost her life insurance and all other assets.

Eva Kappeler knew her husband’s story but when she began to read the individual files, she had to put them aside again and again because tears came to her eyes. To this day she supports her husband in his everyday life and in coming to terms with what he has experienced and makes him angry at times. Eva Kappeler can calm him down and listens to him. Good food is important to both, because Eva Kappeler’s husband has never had that before. Music connects them and so they dance as often as possible, with pleasure also with their grandchildren.

Yvonne Barth

Yvonne Barth talks about:Yvonne Barth

“I worked my way up from nothing.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Yvonne Barth was born in Basel in 1953. Her mother moved again and again and took her two children with her. Yvonne Barth did not feel safe with her. At the age of three, she was sent to the children’s home “Vogelsang” in Basel on monthly basis and in 1958 to a foster family in Davos Wiesen (GR). Yvonne Barth missed her older sister and begged her mother to be placed in the same facility which was arranged in 1961.

Yvonne Barth stayed in the children’s home “Röserental” in Liestal (BL) until she was 12 years old. Here she was often teased by the other kids because she squinted and was walking clumsily due to adhesions on her feet. The girl was not encouraged by the adults: because of her outward appearance, she wasn’t thought of being capable of anything. During this time, animals were important to her: they gave her the closeness and affection that she missed in people.

As an adult, Yvonne Barth continued her education. She trained as a medical massage therapist and opened her own practice. Music always gave her strength – and does to the day. Yvonne Barth was always quick to learn an instrument and still composes her own songs.

She sang her song “Placement in Care from the Perspective of those Children” for the first time in front of an audience at the memorial event for the victims of compulsory social measures in Basel in autumn 2021. It is important to Yvonne Barth to be part of the reassessment – also for all those who are no longer here.

Studio recordings for the song “Placement in Care from the Perspective of those Children”, 22 August 2022.

Katharina Delfino

“When my husband was able to talk about everything, he gained inner peace.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Katharina Delfino was born in Zurich in 1964. Together with her two older brothers, she experienced a carefree childhood. Her parents had their own hairdresser salon where Katharina Delfino helped from an early age. She decided to become a hairdresser too. The training in a hairdressing school was strenuous and accompanied by very long working days, but she got to know a dynamic field of work. With time, she was allowed to go to international shows and also travelled abroad for her jobs, for example to New York or the Philippines.

After a few years, Katharina Delfino needed a break from hairdressing and started to work in a bar in Zurich’s Niederdorf. There she met her future husband, Mario Delfino. When she got pregnant, they moved in together and married. Her husband has told her right from the beginning about his childhood with his adoptive parents and in the facilities. However, she sensed that he couldn’t tell her everything. It was only in 2019 that Mario Delfino revealed to her that he too had been a victim of sexual abuse by Catholic monks.

Together with her husband, Katharina Delfino worked for many years as a caretaker, first in a parish hall, then in a school in the city of Zurich. It is important to her that conflicts and differences are discussed together and that solutions are found together. Her family always takes centre stage for her; they all support each other and are always there for each other.

Michele Delfino

“Because I know what my father experienced, I understand many things better today.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Michele Delfino was born in 1993 in Zurich. He grew up with his parents, Katharina and Mario Delfino. They worked together as caretakers, first in a parish hall and then in a school. In the early years, the family flat was in the same building so that Michele Delfino could spend a lot of time with his parents. At the same time the many rooms and spaces were an ideal playground and place for discoveries. His parents have given him the best conditions for the start in life. He tries to use his opportunities, especially because his father did not have a good start in life.

From an early age, Michele Delfino knew that his father did not grow up at home. He told him repeatedly about individual experiences, for example about his escapes. Later the Delfino family visited the children’s home in Altdorf (UR), the “juvenile correction facility Bad Knutwil” (LU) and the former residence of the adoptive parents in Thalwil (ZH) together.

Michele Delfino suspected that his father could not talk about all his experiences with his family at that time. A few years ago, when they were also able to talk about the sexual violence his father had experienced, this helped Michele Delfino to pin down and better understand his father’s earlier reactions. The things that happened to his father continue to have an effect and influence the next generation; another reason why it is important for Michele that people talk about it.

Christian Tschannen

Christian Tschannen talks about:Christian Tschannen

“They told us: ‘you are nothing, you can’t do anything, nothing will come of you!’”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Christian Tschannen was born in 1971 in the canton of Solothurn. After his parents divorced, the social welfare office got involved and as a result the mother agreed to a temporary placement in care of her children. Christian and his older brother, Benjamin, were sent to Schangnau (BE) to a farm in the Oberemmental where they had to work hard, slept in a small, poorly heated room, were beaten and abused. At the age of nearly nine, Christian suffered from first symptoms of a rheumatic disease which caused him more and more pain.

In 1986, at the age of 15, Christian was placed in the “Jugenddorf” in Bad Knutwil (LU) where he was forced into a carpenter apprenticeship, from which he dropped out. He also experienced violence in the “Jugenddorf” and in the last year was denied medical care and medication. Christian was released in 1989 and completed an apprenticeship as a car-body painter. Due to his illness and his physical impairments, he was registered with the disability pension for retraining. His request to follow a training that took into account his health condition and abilities was not heard by the authorities that decided on disability pensions.

At the age of 24, Christian reoriented himself professionally and studied art at the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts. Among other things, he was Artist in Residence of the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia in Cape Town and has exhibited several times in Switzerland and abroad. With the first official records in 2014, his work changed radically and now sheds light on current affairs. Christian is committed to the reassessment of compulsory social measures and also wants to focus on today’s problematic issues in child and youth welfare services.

From the serial work "Solothurn crime scene images" (2019-2022). Municipality/services of Solothurn. Wound healing plaster on cotton, primed, acrylic marker drawing black/grey. 110cm x 95cm

Sabine Weber*

“My book would have had the title: loving without being loved.”

After a visit, Sabine Weber’s father reported his daughter to the youth welfare office: she was hanging out with men. A false accusation with far reaching consequences: the 15-year-old Sabine was placed in administrative detention. At the first opportunity, she fled from the “Heim Hirslanden” in Zurich to her grandparents in Austria.

Class photo of the 1st class. Sabine Weber* stands directly in front of her teacher. Photo: Private property

After a visit, Sabine Weber’s father reported his daughter to the youth welfare office: she was hanging out with men. A false accusation with far reaching consequences: the 15-year-old Sabine was placed in administrative detention. At the first opportunity, she fled from the “Heim Hirslanden” in Zurich to her grandparents in Austria.

Foto: Mario Delfino

Shortly afterwards, Sabine Weber met a young man in Graz. He too was struggling with having spent his childhood in facilities. Sabine Weber got pregnant. When she entered the hospital to give birth, she signed all papers that were presented to her. However, a doctor pointed out to her shortly before delivery that she was thereby consenting to an adoption as an unmarried woman. The doctor helped her to prevent this.

Later, Sabine Weber moved back to Switzerland. She married but the marriage did not go well. Today Sabine is a pensioner. A progressing eye disease limits her, nevertheless she is active, enjoys life with her current partner and tries to do as much as possible independently.

*The name was replaced by a pseudonym.

Michael

“A children’s home is not a home – and educators are not parents.”

Foto: Mario Delfino

Born in Zurich in 1964, Michael was the third child of very young multi-addicted parents. To this day, he doesn’t know how many siblings he has. His grandparents cared for the boy until the guardianship authorities of the city of Zurich took him away from his grandmother after the death of his grandfather – even though she would have liked to keep him with her. First, Michael was placed in various foster families and at the age of 9 in the children’s home Heizenholz in Zurich-Hongg. He experienced educators who responded to him and others who were violent. What he lacked was a contact person to whom he could turn to when he had questions or concerns. Even after his release he would have liked to have a contact person to turn to for example regarding questions about money or taxes.

After completing the compulsory schooling, Michael was threatened to be interned again in a home in the west of Switzerland if he didn’t find an apprenticeship quickly. During his training he lived in a studio and managed everyday life independently. In 1984, Michael was released from guardianship. He went his own way, found friends, started a family and experienced joy in his professional everyday life. Michael talks openly about his childhood, also to his daughter. It is important to him that he does not pass on what he experienced to her and thus breaks the circle of violence. Coming to terms with the experienced injustice and acknowledging it, he considers as very important: for those affected but also for society.

Michael and his daughter Julia skydiving, 2019 Photo: Private