Education & Profession

Defined goal of many coercive welfare measures was to “educate” or “re-educate” for work. For a long time, social advancement due to good education was not foreseen. The promotion of individual fortes often came up short. However, those who got promoted had a better starting position later in their professional life.

A Career Was Not Intended

Work was often in the foreground during administrative detention or placement in care. Therefore, many children and adolescents experienced a disadvantage regarding their school education. Their talents were hardly promoted.

For a long time, their possibilities of education were limited and only unskilled work in agriculture or housekeeping was open to them. In comparison to adolescents who did not grow up in foster care, these young persons faced a disadvantage. To make up for what they had missed and to be able to lead a self-determined professional life, those affected later had go to great lengths. ...

Individual Support Often Had to Take a Back Seat

To choose one own’s professional path was for persons who were placed in care not a given fact for a long time. Instead, their choice was very limited and furthermore adhered to rigid gender roles that only slowly were softening.

Front page of a printed leaflet from the reform facility for girls “Anstalt vom Guten Hirten” from 1914.

For a long time, the upbringing and education of girls was equivalent to preparing them for a life as housewife and mother, even though in reality many families were dependent on a second income. For instance, the leaflet from the reform facility for girls “vom Guten Hirten” around 1914 also promoted the strict education within a specific gender role – prominently placed on the front page. To be sure, the leaflet emphasised that the young women were promoted according to their abilities. However, to secure the funding of this home, ”the main part [of the young women] are used for manual labour”. This immediately put the previous statement into perspective.

Disadvantages in Old Age

Disadvantages in education can affect not only the later working life but also the pension: they increase the risk of old-age poverty.

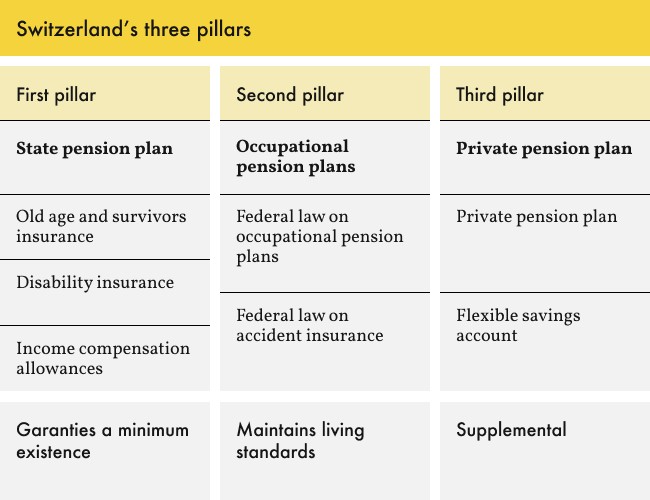

The Swiss pension system is based on three pillars: old-age and survivor’s insurance (1st pillar), occupational pension (2nd pillar), private pension (3rd pillar).

The AHV depends on the number of years somebody paid in. Contribution gaps lead to a partial pension. Each missing contribution year entails a reduction of approx. 2.3 percent. The maximum pension of currently 2,390 Swiss francs per month requires an average yearly income of slightly more than 86,000 Swiss francs. The minimum pension amounts to 1,195 Swiss francs. If a pension is not enough to live on, supplementary benefits can be applied for. Many of those affected do not do so – out of fear to be dependent on the state again.

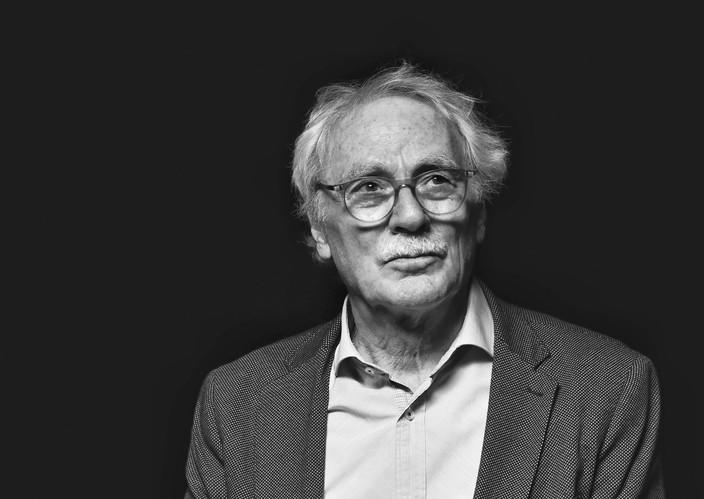

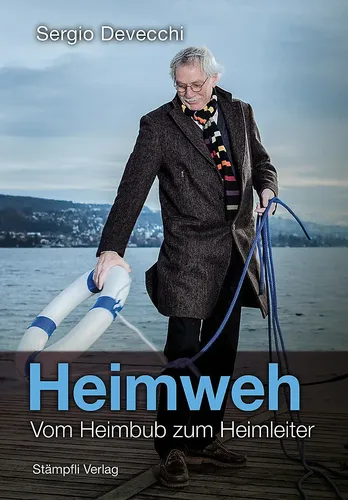

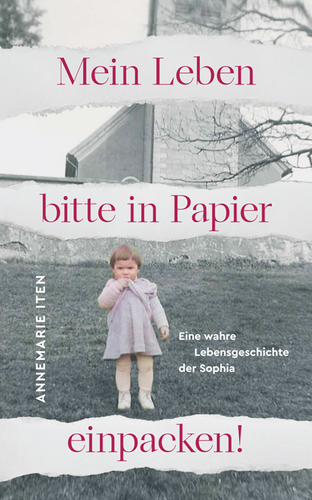

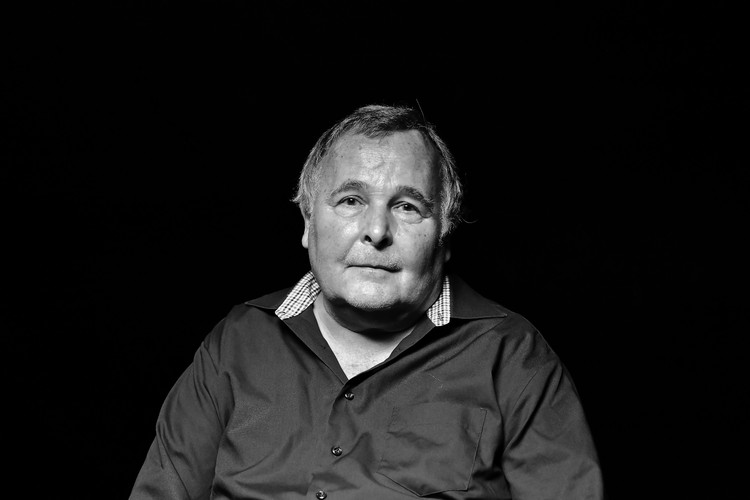

We Talk in this Film

A Career Was Not Intended

Work was often in the foreground during administrative detention or placement in care. Therefore, many children and adolescents experienced a disadvantage regarding their school education. Their talents were hardly promoted.

For a long time, their possibilities of education were limited and only unskilled work in agriculture or housekeeping was open to them. In comparison to adolescents who did not grow up in foster care, these young persons faced a disadvantage. To make up for what they had missed and to be able to lead a self-determined professional life, those affected later had go to great lengths. ...

Work and Education

For a long time, everyday life in care placements was mainly about work. Children, adolescents or adults: all had to work, many facilities had a farm, or a big garden as well as attached workshops. Some were called upon to work at a factory. School and education, however, were neglected. For example, school attendance was often cancelled during harvest time.

And because social advancement through education was not envisaged for internees, they usually just finished compulsory school. Foster care children were intended to become farmhands and maids or unskilled labourers. In the interwar period the facilities began to react to developments in society as a whole and gradually introduced vocational apprenticeships. However, the choice remained limited and in line with gender-specific job profiles. Young men, for instance, were trained as gardeners, locksmiths and carpenters, while young women could choose to become women ironers or laundry women.

Children and adolescents were often placed in farming families where they were used as labour force from childhood on. Until well into the 20th century, there was almost no agricultural machinery used and the demand for cheap manpower accordingly high. In some regions these children were called “Verdingkinder” or “Kostkinder”. At the end of their compulsory schooling, they usually had hardly any training opportunities. For a long time, vocational educations cost money, i.e., they were not possible if the financial resources were lacking. Only during the 1970s, the range of training possibilities grew wider and access to higher or self-selected education was also more feasible. Now young women too could learn a profession that had previously been for men only and some facilities even allowed external training.

Diverse Professional Biographies After the End of the Placement

The professional paths of people who experienced coercive welfare measures and placements in care are very diverse and varied. What almost all have in common is the difficulties they were confronted with in their professional life due to insufficient schooling and professional training. In fear of stigmatisation, many of them created incomplete or false CVs; nobody was to know where they had grown up.

After years in heteronomy, most of those affected strived for autonomy in their professional life. If their finances permitted, they tried to catch up on education they had missed, started apprenticeships, attended further trainings or started to study. Thereby they wanted to improve their chances on the job market and achieve professional and social integration. Encouragement and support of superiors or professional colleagues could be particularly important in this respect.

However, due to the stigmatisation, lacking education and health consequences resulting from the traumas experienced, professional advancement was denied to many of them. Poorly paid jobs, instable working conditions and gaps in pension provisions were the result. This had effects right up to old age: low wages led to low pensions, so that many of those affected had to live in precarious circumstances after the end of their career and still do so. Moreover, out of distrust and fear to be dependent on the state once again, many don’t apply for supplementary benefits.