Fundamentally Unprepared

The victims were hardly prepared for the time after the coercive social or foster care measures. For a long time, there was hardly any support on the way to an autonomous life and support is still insufficient today.

And the Sword of Damocles Always Hovers Over the Happiness

Victims of a social measure had only limited influence on when it would come to an end.

An important age limit was the coming of age, which was 20 until 1996. But this was not always the end of the official intervention. If a life was considered not conforming to society, there was the imminent risk of new measures. At the same time support services that were perceived as such were rare and the road to an autonomous life not seldom rocky. Not all managed, many committed suicide because they could not cope with what they had experienced. ...

Support Makes All the Difference

People who help others without asking where they come from can be decisive for their future life. People affected by social measures also found support again and again and manged to arrive in their own life.

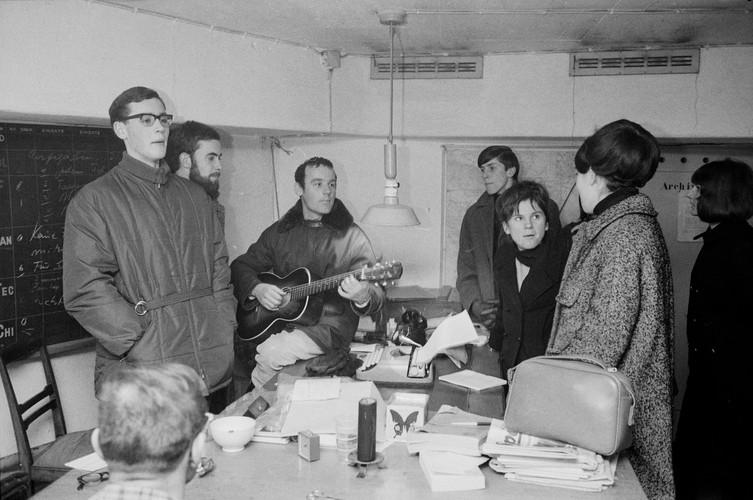

In winter 1963, the last time Lake Zurich froze over, pastor Ernst Sieber established an emergency sleeping facility for homeless in an old bunker. Photo: Jules Vogt

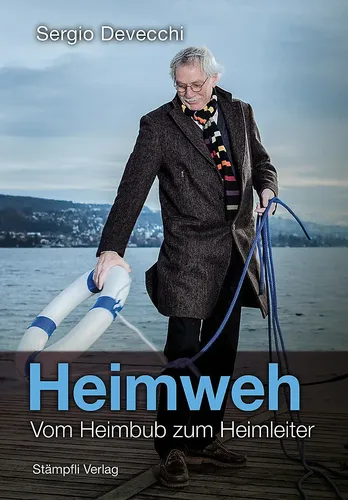

Since the 1960s, the Zurich pastor Ernst Sieber committed to support people who had been pushed to the margins of society. He was “streetworker” and “pastor of the homeless”. Sieber founded, among other things, the “Christuszentrum”, a residential community for stranded youths, many of whom had been brought up in children’s homes. They called their new home “shack”. Mario Delfino was the first resident.

Today Too: Not Prepared for Life

The lack of support on the way to an autonomous life is still an issue.

At the age of 18 one is now of age and state support ends for those who grew up in a home or a foster family. With the new rights also come obligations. On the way to an independent life, there are questions concerning moving out, job or money. To support young adults, people who themselves haven’t grown up with their birth family organise themselves ("Care Leaver").

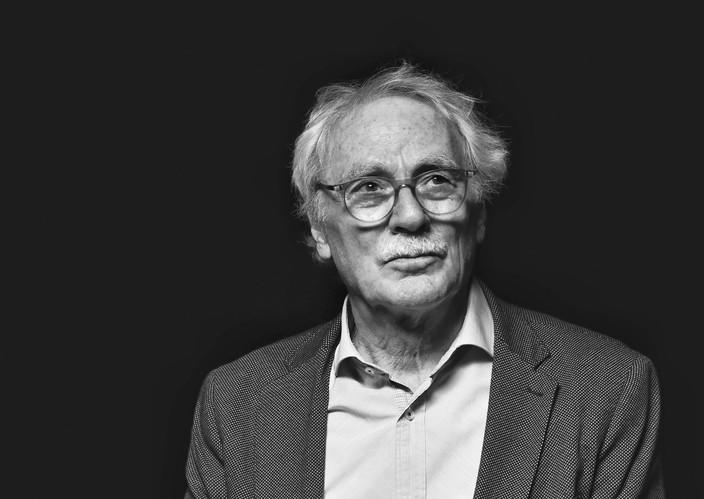

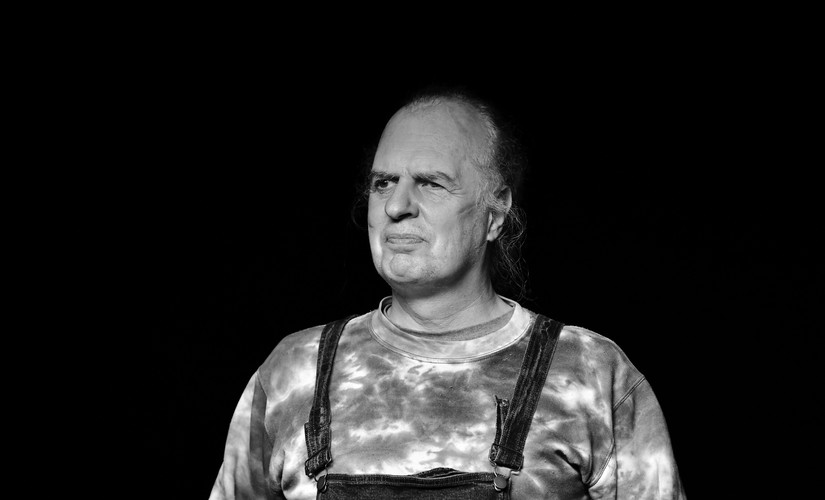

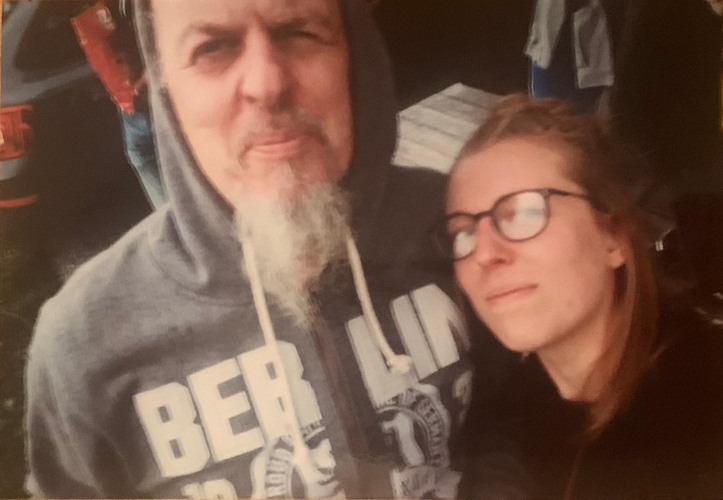

We Talk in this Film

And the Sword of Damocles Always Hovers Over the Happiness

Victims of a social measure had only limited influence on when it would come to an end.

An important age limit was the coming of age, which was 20 until 1996. But this was not always the end of the official intervention. If a life was considered not conforming to society, there was the imminent risk of new measures. At the same time support services that were perceived as such were rare and the road to an autonomous life not seldom rocky. Not all managed, many committed suicide because they could not cope with what they had experienced. ...

Release Into Freedom

On the way to a self-determined life, the affected persons were dependent on the judgment of individual authorities: In the institutions it was the head of the home, the “home father” or the matron who mainly decided on the time of release and any conditions. Together with the psychiatric assessment, their assessment formed the basis for the decision of the referring authorities and the guardians.

The decisive factor for the assessment was the “improvement” or “probation” of a person since admission, i.e., whether somebody had subjected him- or herself to the institutional regime. Thus, the management of the institutions and homes possessed a great deal of power. Some private organisations also secured the right of determination over children and adolescents in care by getting parents to sign declarations of assignment in exchange for the accommodation costs.

In combination with the ill-defined release criteria, this resulted in arbitrary decisions. It was only in the post-war aera that the power of the management of the homes was partially broken and expert commissions were set up to assess the internees.

Release often did not mean absolute freedom. Many people were under supervision by a parole officer: they were accompanied and observed. In many cantons this function was assumed by officials. Thus, the parole took place between the poles of subsequent support and coercion to lead a socially conforming way of life. A negative assessment bore the threat of re-institutionalisation.

In Search of a Place in Society

For many of those affected release came unexpected. Suddenly they were on their own and had to decide for themselves after years of heteronomy. They had hardly been prepared for the challenges of everyday life during their placements in care. Many of those affected had nothing on the day of their release: no contact with their birth family, no money, no flat, no friends, no job, no prospects. This fact is still relevant today, as the current discussion concerning the so-called “care leaver” who spent their childhood in a home or with a foster family shows.

Finding a place in society was difficult for many of them and often took years. The feeling of not being welcome and not belonging to society was pronounced. Those affected often had lost their social contacts and building new relationships was not easy. The fear of being stigmatised and rejected because of their past caused many to keep quiet about the experienced. More than a few turned to alcohol or drugs, hit the road and came into the focus of the authorities once again. Others committed suicide.

A social network after release was important. Some could count on the support of parents or relatives. They took them in after their release and found them their first jobs. Others made happy acquaintances in private life or encountered, for example, a social worker or superior who supported them in further shaping their life path. This way many succeeded in getting a foothold in life. Of central importance in this process, which often took years, was that those affected were recognised as persons with their own abilities and given a chance.