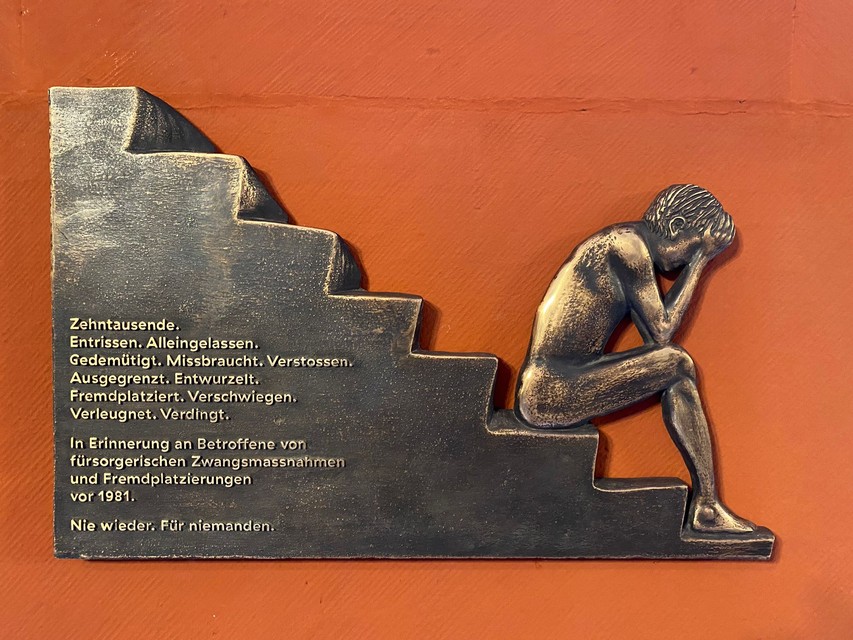

Suppression

To talk about difficult and traumatising experiences takes courage. Many of those affected have suppressed their past. Society too has ignored the fates of the people affected by coercive welfare measures or care placements for a long time. The reassessment of the injustice that is now underway is painful – for those affected and for society.

The End of Silence

Already early on welfare measures under duress or confiscation of children were criticised. But the response was modest and the changes too.

Social measures and placements in care were part of Swiss social and family policy. They were based on a broad range of legal provisions and followed a social need for security. That these boundaries of the norm had been set very narrowly and individual needs were disregarded for a long time is difficult to understand from today’s perspective. ...

Late Socio-Political Reassessment

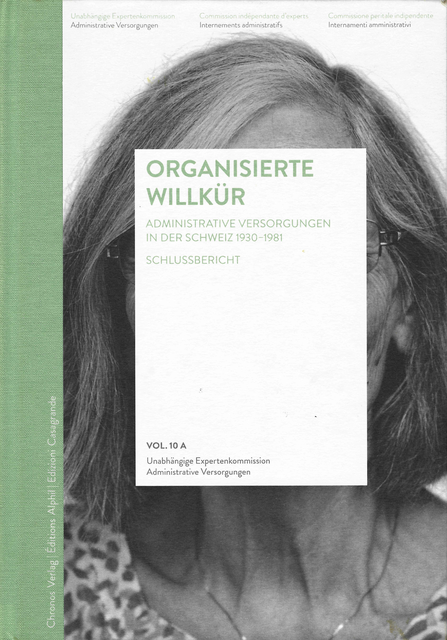

After several setbacks, the debate on coercive social measures and placements in Switzerland has now been present in the media for several years and is addressed by policy, society, culture and science. Key thereby were and are the voices of those affected. Attempts to reassess the injustice of the past have been made earlier in other countries, for instance in Canada, Australia, Germany, Austria, Sweden, Norway or Belgium.

And Everybody Played Along – Really Everybody?

Coercive welfare measures could persist for so long because they were supported by society and decision makers. But there were also always critical voices. One of them was Carl Albert Loosli.

Carl Albert Loosli in an undated photograph. Photographer: unknown.

An early and vehement critic of administrative welfare measures under duress and discrimination was the Bümpliz poet and writer Carl Albert Loosli. With a sharp pen he wrote against such discrimination and the “administrative justice”.

We Talk in this Film

The End of Silence

Already early on welfare measures under duress or confiscation of children were criticised. But the response was modest and the changes too.

Social measures and placements in care were part of Swiss social and family policy. They were based on a broad range of legal provisions and followed a social need for security. That these boundaries of the norm had been set very narrowly and individual needs were disregarded for a long time is difficult to understand from today’s perspective. ...

Between Suppression and Reassessment

Those affected often do not talk about their experiences for a long time. And if they do so, it is usually only in fragments and within the closest circle of family and friends. Many have had painful and traumatic experiences due to placements in care or social measures. They suppress their past out of shame or fear of being stigmatised again. Behind this is the desire to forget and leave the experiences behind.

To break through the wall of silence and confront one’s own past requires courage. The support of relatives, friends and professionals can be helpful. The search for answers about one’s origin or reasons for the social measures often leads to one’s own files. Many experience the confrontation with the official files as a moment of shock: not only the derogatory language of the authorities or psychiatrists, but also the defamations and denunciations from the environment can throw them off track.

The more affected people go public with their stories, the more others feel encouraged to follow their example. Only the visibility that emerges from this enables a public discussion about the injustice they suffered.

Social Reassessment

In Switzerland, the public simply accepted the fate of people who were placed in care or cared for under coercive measures for decades. Early on there were critical voices to be heard, among them famous persons such as Jeremias Gotthelf, Carl Albert Loosli or Peter Surava. But their criticism never led to more than a short-term media outcry in drastic cases of abuse. Liberal and humanitarian Switzerland did not allow any discussion on this topic.

The social point of view began to change only in the 1970s, and in the 1980s the practices of the “Hilfswerk für die Kinder der Landstrasse” were investigated which led to the first apology by the Federal Council and to compensation payments.

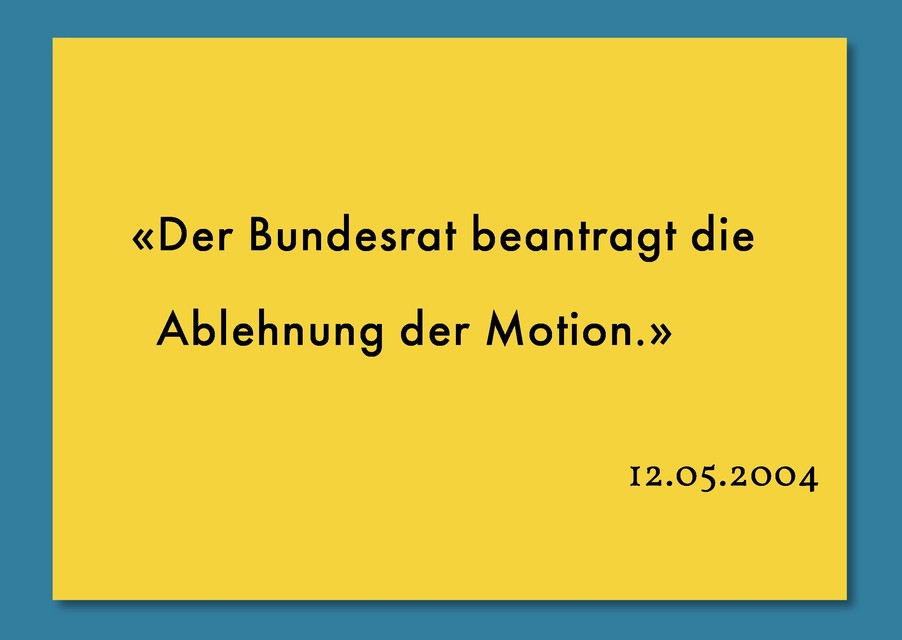

However, while several western countries lanced initiatives to historically reassess the forced placement of children, it remained silent in Switzerland. It was not until the beginning of 2000s that former victims managed to make themselves heard with the support of representatives from media, science, politics and culture.

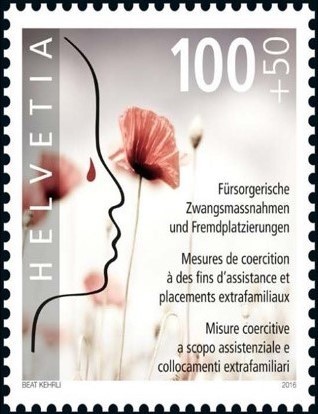

In 2010 and 2013, the Swiss government acknowledged the suffering the victims had experienced and asked them for forgiveness. Representatives from the cantons, municipalities, church and private organisations followed. Between 2014 and 2019, an independent commission of experts examined the practice of forced placement of children on the behalf of the Federal Council. The scientific reassessment continues to this date within the framework of a national research programme and through investigations commissioned by cantons, institutions and organisations.

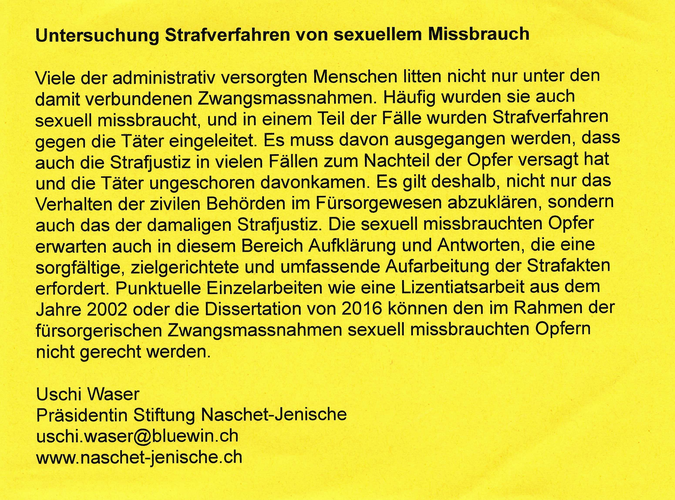

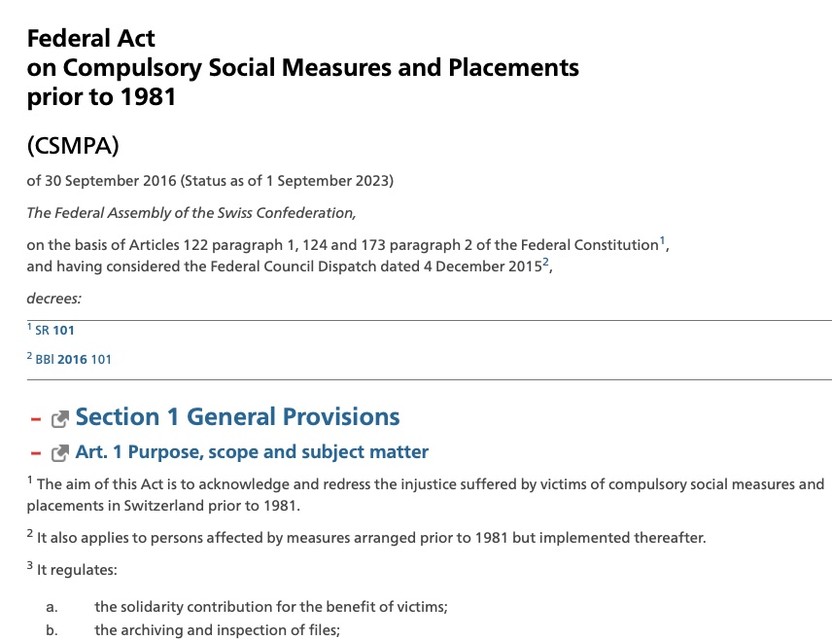

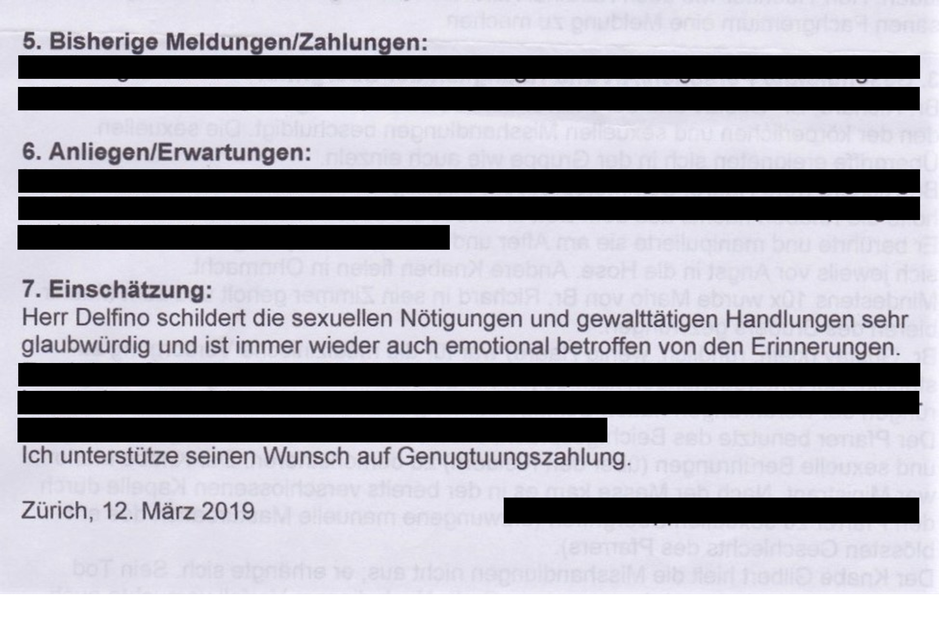

The reassessment also raises the question of reparation. In April 2017, a law became effective that provides, among others, a so-called solidarity contribution of 25,000 Swiss francs per affected person. Until the end of December 2021, more than 10,000 persons had filed an application. Whether this can make up the injustice committed and how the socio-political reassessment should be shaped to last – is a matter of differing opinions. The expectations of the politicians and authorities collide with those of the victims who in turn have different demands regarding the reassessment and reparation process.