Uprooting & Loneliness

The feeling of being uprooted and alone was familiar to many who were placed in care or interned. Loneliness was their constant companion, even when they were surrounded by people. The contact to their family or siblings wasn’t always possible, visitors came rarely and for a long time friendships were deliberately prevented.

Far Away from One’s Own Life

In case of administrative detention or placement in care, those affected lost their family and social surrounding. Accommodation in places that were far away from home further promoted the feeling of isolation.

The separation from the familiar surroundings and the placement of siblings in different places was a deliberate act to prevent their mutual influence, which was assessed as negative. For a long time, this practice was favoured by limited mobility: having one’s own car was not a matter of course until recent years and train journeys were often too expensive. Visitors were also rare and only with time not every letter was checked anymore ...

Placed Anew Again and Again

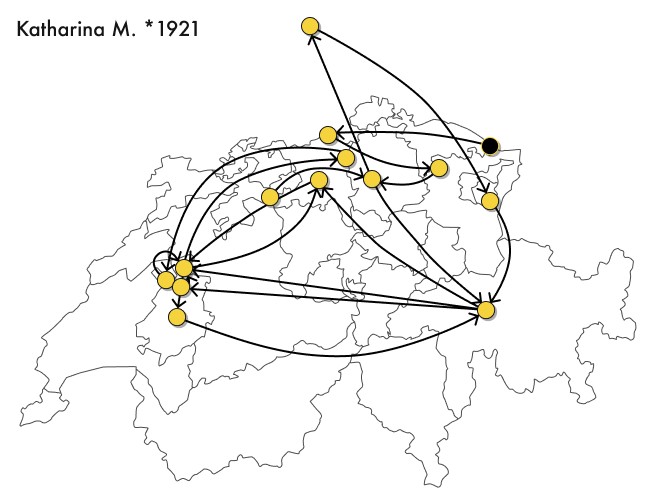

Not seldom, those affected experienced different compulsory social measures and several placements. This reinforced the feeling of being nowhere welcome and being at the mercy of arbitrariness.

Crèche Arbon (TG), 1927; foster family Koblenz (D), 1927; home of St. Idda, Lüttisburg (SG), 1929; girl’s home Tannenhof, Zurich, 1936; psychiatric polyclinic, Zurich, 1936; Guter Hirt, Strassburg (F), 1936; Guter Hirt, Altstätten (SG), 1936; Realta, Cazis (GR), 1936; Dienststelle, Fulenbach (SO), 1937; girls home Tannenhof, Zurich, 1937; Monikaheim in der Hub, Zurich, 1937; Zurich public authorities, 1937; Realta, Cazis (GR), 1937; Bellechasse, Sugiez (FR), 1939; Oberehrendingen public authorities (AG), 1940; Guter Hirt, Lully (FR), 1940; asylum Belfaux (FR), 1943; Marsens (FR), 1944; Beverin, Cazis (GR), 1944; Realta, Cazis (GR), 1944; Bellechasse, Sugiez (FR), 1944; Niederlenz public authorities (AG), 1945; Bellechasse, Sugiez (FR), 1948

There were many reasons for a re-placement. One of them was maladaptive behaviour which also included escape attempts. Between 1927 and 1951, Katharina M*. was subjected to a total of 24 placements in children’s homes, psychiatric institutions, “forced labour institutions”, prisons, with foster parents and public authorities, not only throughout Switzerland but also in Germany and France. Her father had placed her and her siblings in a children’s home in Arbon (TG) after the death of her mother. The head of the organisation “Hilfswerk für die Kinder der Landstrasse”, Alfred Siegfried, became their guardian.

Katharina M.* became a mother at an early age and tried to make a living for her and her children – until she was interned once again. At the age of 30 she moved in with her father and no further social measures are known. Whether she ever saw her children again, who had been taken from her, remains unknown.

“You can’t get any lonelier”

Homesickness hurts. Separation from the familiar surroundings is difficult, especially for children and adolescents.

As a child Uschi Waser was placed in 20 different homes and with 4 foster families. At the age of 15 she wrote the poem “A Mother's Love”. At that time, she was administratively cared for at the juvenile correction facility for girls “Zum Guten Hirt” in Altstätten (SG).

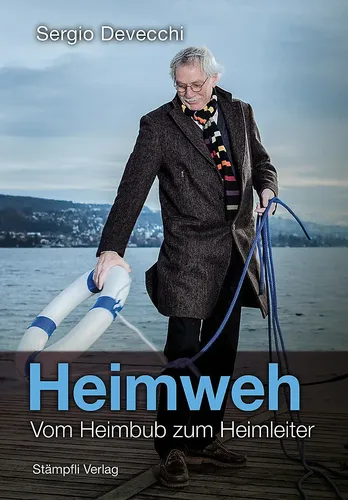

We Talk in this Film

Far Away from One’s Own Life

In case of administrative detention or placement in care, those affected lost their family and social surrounding. Accommodation in places that were far away from home further promoted the feeling of isolation.

The separation from the familiar surroundings and the placement of siblings in different places was a deliberate act to isolate them from “negative influence”. For a long time, this practice was favoured by limited mobility: having one’s own car was not a matter of course until recent years and train journeys were often too expensive. And only with time not every letter was checked anymore ...

Isolation and Loneliness

Often the facilities were situated outside a village, and, depending on their function, they were secured. Some home directors propagated the physical separation from the outside world as protection from harmful influences. The separation of siblings sometimes resulted in them not knowing about each other. Especially Yenish families were systematically torn apart: between 1926 and 1972 the aid organisation “Hilfswerk für die Kinder der Landstrasse”, run by Pro Juventute, placed more than 600 Yenish children in homes and foster families – with the aim to put a stop to the travelling way of life. But the isolation and remoteness could also be used to secretely give birth to a child, for example in the mother-child home “Foyer St. Joseph” in Belfond (Jura).

Not all cantons had a differentiated range of facilities, thus people were being placed beyond the borders of a canton in other parts of the country. Visiting days were scarce for a long time and visiting bans were a common punishment for rule violations. In many places visits were only possible under observation by the home staff.

Guardians or caregivers seldom came by and only very rarely had a trusting relationship with their wards. Their visits were mainly due to financial or organisational matters that had to be settled. As friendships with others were rarely possible, those affected grew lonely within the collective of “institutional life”: people came and went – where to was seldom communicated. Those who found a connection to an educator or an employee and experienced emotional closeness were lucky.

Writing Against Loneliness and Alienation

Often, letters were the only connection to the outside world. For some writing worked as a valve. It helped to overcome the loneliness at least temporarily. Besides, with letters they could also ask their relatives for material goods that were missing or lacked in the “facility”, such as soap, tobacco or food.

Like the possibility of visitors from outside, the postal traffic was also controlled: until the 1970s, a strict mail censorship prevailed in most facilities. The staff opened the letters of the internees and, depending on the content, withheld them or sent them on to the official offices. Censoring the letter was not only an intrusion into the privacy of the internees, but in certain cases also violated their individual rights. For it was not uncommon that the communication with their legal representation was prevented due to postal censorship.

The restriction and active obstruction of contact with families and friends, as well as the supression of human relationships in the “facilities” and homes, marked those affected well beyond the end of a coercive measure. Socially isolated and without relationship network, they were released into freedom. Many did not know where their parents lived, let alone if they had brothers or sisters. The feeling of loneliness and abandonment remained present, often for a whole lifetime.